- Joined

- Aug 4, 2016

- Messages

- 736

- Reaction score

- 405

Kakutogi Road: The Complete History of MMA Volume 84 "Paradigm Shift"

“There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen.” – Vladimir Lenin. (And in the world of combat sports, few weeks have packed more decades' worth of change than those leading up to November 12, 1993.)

MB (Michael Betz): Every generation feels a shift—an invisible ripple in the air that begins as a murmur before swelling into an unstoppable current. These shifts arrive without warning, as arbitrary as the wind, yet their impact reshapes history. For years, we at Kakutogi Road have been tracing these undercurrents—the quiet revolution that began within the rings of Japanese pro wrestling, where the foundation of modern MMA was first laid. But Japan’s evolution, though groundbreaking, was insular. It unfolded within the puroresu ecosystem, seen only by diehard fans willing to sift through grainy tapes or scan the pages of obscure fight magazines.

America’s awakening would be different. It would be loud, brutal, and televised.

For anyone under 35, it's almost impossible to comprehend how shrouded in mystery the martial arts world was in 1993. This was a time before YouTube breakdowns or leaked sparring footage—when the average person’s understanding of a "real fight" was shaped by action movies, pro wrestling, and martial arts magazines. Sure, boxing and wrestling existed, but they felt like isolated islands in a sea of speculation. The notion of what actually worked in a fight seemed like an esoteric secret, guarded by those who knew, and unreachable to the rest of us.

ML (Mike Lorefice): It was a time when the debate of pro wrestling being worked was finally coming to an end after only 7 decades, when boxing still reigned supreme because it was the only high profile combat sport. Most notions of fighting were still based upon flashy movie action scenes, where it took decades to evolve from untrained actors such as James Cagney or John Wayne knocking people out with one improperly thrown, incredibly telegraphed punch to real martial artists such as Bruce Lee and Chuck Norris utilizing an endless array of spinning and flying kicks to take out gangs of henchman singlehandedly because the stuff they actually did in karate tournaments wasn't deemed to be marketable enough to sell movies tickets. The ninja craze of the 1980s hadn't yielded much to elevate the credibility of fighting either, instead conjuring silly debates about Chinese throwing stars being more effective than bullets because stars couldn't be caught in your teeth. Frank Shamrock probably captured the collective martial arts knowledge of the public best when he mentioned, "I'd watched Chuck Norris (movies), and that was it."

MB: We knew the truth was out there—but how could we get to it?

Yet, cracks were beginning to form in the matrix.

Films like Bloodsport (1989) and the explosive popularity of Street Fighter II (1991) had ignited something. They stirred imaginations and fueled debates that rang out across playgrounds, gyms, and military barracks. The questions were universal:

"Could a wrestler beat a boxer?"

"Was karate really as deadly as the movies made it seem?"

"Was devoting your life to kung fu wisdom, or folly?"

These weren’t just idle questions. For many of us, they mattered. They gnawed at something primal. We didn’t want theory—we wanted proof.

And in November of 1993, thanks to a relentless visionary named Art Davie, the world would finally get its answer.

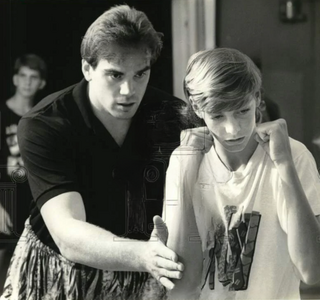

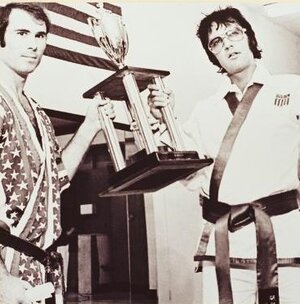

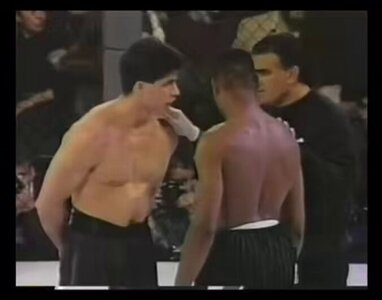

Art Davie alongside Rorion Gracie

Davie was born in Brooklyn on April 6, 1947. He was the driving force behind what would become the Ultimate Fighting Championship—an event initially pitched under the grandiose title War of the Worlds. An amateur boxer in his youth, Davie’s journey toward this moment began in 1965, when he was humbled by a wrestler during a friendly sparring session. They were of similar size, but that didn’t matter. The wrestler put him on his back and rendered him helpless. No punches, no counters—just the suffocating truth of physical dominance.

That encounter lodged itself deep in Davie’s psyche. Years later, while serving in the Marine Corps, the same questions resurfaced during endless barracks debates about fighting styles. These weren’t casual conversations. They were theoretical wars, waged over beers, boredom, and bravado.

But for Davie, this was never just talk.

After leaving the military, he built a career in advertising—becoming a sharp, audacious copywriter known for bold campaigns that demanded attention. Yet his fascination with combat never waned. He watched the bizarre spectacle of Muhammad Ali vs. Antonio Inoki, the stunt fights of Chuck Wepner, and the grappling feats of Gene LeBell. These mismatches were messy and awkward, but they hinted at something profound:

Style vs. Style.

There was a spectacle here—and a truth—waiting to be uncovered.

He began pitching his idea: A no-holds-barred tournament—real fighters, real styles, one night, one winner. But every meeting ended the same way. Ad executives smirked, executives balked. Too brutal. Too risky. Too far-fetched.

What Davie needed was a spark.

He found it in Rorion Gracie.

Davie first heard the name in 1989, reading a Playboy interview that introduced the Gracie family’s Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu to the wider world. The Gracies claimed their style was superior to all others, and they had the underground “Gracie Challenge” fights to prove it. Davie was hooked. He sought out Rorion Gracie, trained with him, and pitched his vision: Let’s settle this once and for all—on Pay-Per-View.

But Rorion didn’t bite.

To him, Davie was just another fast-talking hustler with a dream and no credentials to back it up. Gracie had heard it all before. He had no reason to believe this would be any different.

But Davie was persistent.

He noticed that Rorion’s Gracies in Action tapes—showing jiu-jitsu dismantling other martial arts—were popular but confined to a niche audience. Davie made an offer: Let me handle your marketing. He crafted an ad campaign, and the sales exploded, generating $150,000 in profit.

Suddenly, he had Rorion’s attention.

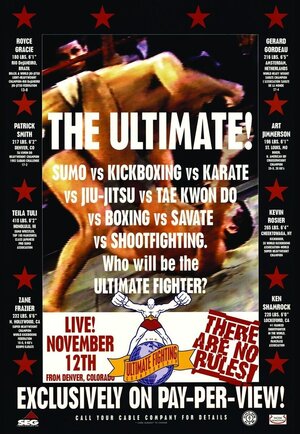

With John Milius—the Hollywood screenwriter and director best known for Conan the Barbarian and Red Dawn—joining as an ally, the dream began to solidify. Davie created an LLC in Colorado, exploiting a legal gray area that allowed for no-holds-barred fighting. He then secured a deal with Semaphore Entertainment Group (SEG), a Pay-Per-View company willing to gamble on blood and chaos.

ML: Colorado was chosen due to the lack of an athletic commission, but the altitude made it arguably the least desirable location for the fighters to compete in a tournament, especially one that was short notice for most of them, that they didn't know whether would actually happen, or if it would really be real fighting.

MB: The budget was $750,000. The stakes were far higher.

Now, Davie needed fighters. He scoured dojos and gyms, hunting for men who could represent their styles with legitimacy. He needed karate masters, boxers, wrestlers—representatives of the martial arts world as it had existed in myth.

Every selection had to pass through Rorion, though he was largely indifferent—unless the fighter was a grappler. Those were the threats. Those were the men who might ruin the Gracie coronation.

Because make no mistake—Rorion wasn’t seeking competition. He was seeking confirmation.

ML: Davie had admirable goals of proving theories and exposing years of stylistic propaganda. He did his best to give fighters a venue to prove themselves, the problem was he needed Rorion to make it happen, and to Rorion, it was all a Gracie Jiu Jitsu infomercial. Rorion liked how much more money he was making from video tape sales, and with this well calculated tournament designed to crown his style of fighting as the one true combat necessity, students and instructional sales were poised to go through the roof. He wasn't going to make the mistake his father Helio did, seeing his style defeated by judoka Masahiko Kimura. Though Davie initially pursued then 2 time Greco-Roman champion Aleksandr Karelin, who he had no chance of affording, he was quickly informed by Rorion that wrestlers weren't allowed. That meant no offers to Mark Coleman, Mark Kerr, Kevin Jackson, Dan Severn, Dan Henderson, Randy Couture, Mike Van Arsdale, Dennis Koslowski, etc. While BJJ was designed to still work off your back, crucial to the Gracie's success over the course of 3 fights was getting on top of his opponent, and Royce seemingly only had one double leg takedown that he dropped down into off of his annoying side kick. If that failed, he hoped to maintain the clinch until he could trip the opponent up. Do you think this simplistic grappling sequence would have worked against Coleman or Kerr, especially after they'd seen it earlier in the night, or that they weren't taking him down and bashing his skull in??? Rorion certainly wasn't confident. Still, in typical Gracie fashion, they weren't honest about it either. Zane Frazier found the casting to be dubious, and questioned Rorion about it the day before the show. “We were going to compete in Colorado, right near the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, and there were no wrestlers involved? I remember at the fighter meeting before the event, Rorion told me all the wrestlers declined to fight.”

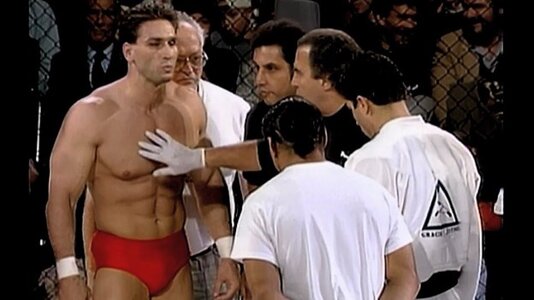

Davie wasn't encouraged to pursue anyone trained by any of the other Gracie's either, so Carlos' students such as Mario Sperry weren't considered, nor were Gracie rivals such as the Machado Brothers or Luta Livre expert Marco Ruas. This may have been presented to Davie under the guise of Royce being the Jiu Jitsu representative. This was very much an invitational, with the invitations designed to prove one very specific point. Davie's final field of fighters somehow included an American sumo wrestler, the existence of which one can seemingly count on fingers, but only high school wrestler whose career ended due to breaking his neck turned Pancrase shootfighter 2 months earlier, Ken Shamrock, had any notable training in any ground based combat sport (wrestling, jiu jitsu, judo, sambo, etc). Future UFC matchmaker John Perretti described UFC 1 on the Lytes Out Podcast as being "A disgusting infomercial, at best", and likes to call the early UFC matchmaking “purposeful mismatches”. Royce Gracie's opponent kept changing until they settled upon arguably the weakest fighter in the field.

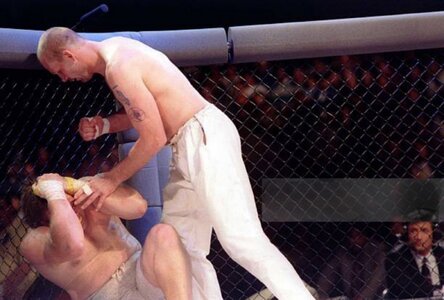

MB: Gracie Jiu-Jitsu was undefeated. It had conquered all challengers in gyms and behind closed doors. Now, Rorion saw UFC 1 as the ultimate stage to showcase his family’s dominance.

What he didn’t realize—what none of them realized—was that this event wouldn’t just crown a style. It would tear the veil from the martial arts world.

The force field was about to break.

(To be continued in next post)...