- Joined

- Jan 17, 2010

- Messages

- 12,662

- Reaction score

- 15,592

Alaska’s Frigid North Slope Was Once a Lush, Wet, Dinosaur Hotspot, Fossils Reveal

Conditions north of the Arctic Circle, where dinosaurs roamed in abundance during the mid-Cretaceous, were warmer than today, with rainfall comparable to “modern-day Miami”

Christian Thorsberg Daily Correspondent

March 20, 2024

Boreal forests, spongy tundra and perpetual sunshine mark summertime in Alaska’s North Slope—the state’s northernmost region, which borders the Arctic Ocean. And when autumn comes, the landscape transforms into a snow-covered darkness, a harsh place endured throughout winter and spring by both people and wildlife.

But 100 million years ago, the dinosaurs roaming this region didn’t have to contend with the frigid conditions of present-day Alaska, according to a study published in late January in the journal Geosciences. Instead, the researchers say, mid-Cretaceous Alaskan climates were warmer, rich in groundwater and more reminiscent of today’s tropics than the Arctic, at least in terms of rainfall.

Scientists uncovered a large swath of fossilized dinosaur tracks, plants, feces and tree trunks in the foothills of the DeLong Mountains along the Kukpowruk River in the state’s northwest—well within the Arctic Circle. From these preserved remains, the team of paleontologists and geologists could construct a picture of the mid-Cretaceous climate and dinosaur life.

“We were at a spot where we eventually realized that for at least 400 yards, we were walking on an ancient landscape,” study co-author Anthony Fiorillo, formerly a paleontologist at Southern Methodist University and now executive director of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, says in a statement. “We found large upright trees with little trees in between and leaves on the ground. We had tracks on the ground and fossilized feces… It was just like we were walking through the woods of millions of years ago.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a6/fe/a6fed9a2-2714-42b1-aa0c-97e377b98114/alaskadino3.webp)

A ten-centimeter-wide theropod track found along the banks of the Kukpowruk River. Anthony Fiorillo

Researchers analyzed rocks, preserved logs and plant material, learning the area was once a network of rivers or deltas and floodplains. Fossilized tree stumps, some as wide as two feet in diameter, hinted at a former thick forest.

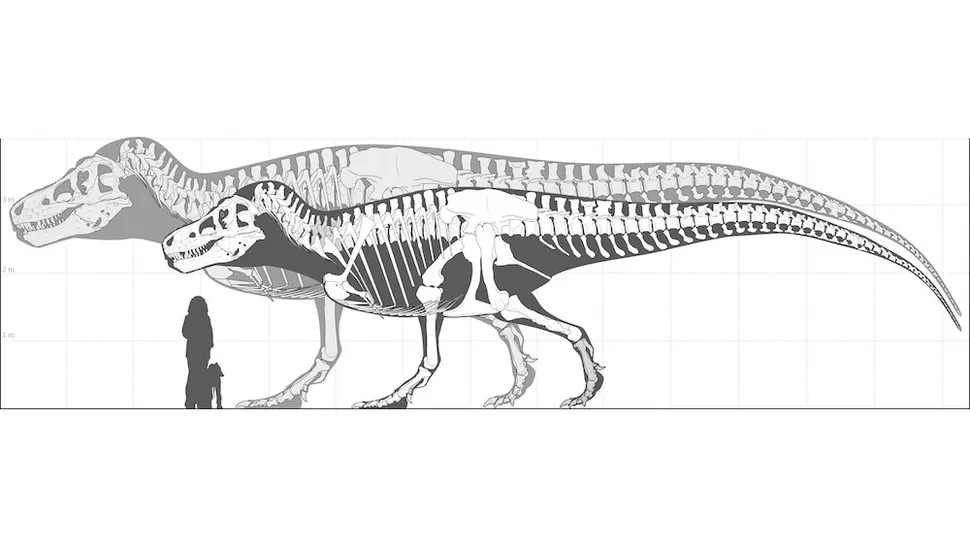

The site was also “crazy rich with dinosaur footprints,” says Fiorillo in the statement. Roughly 75 fossil tracks indicate the relatively warm area supported plant-eating and carnivorous dinosaurs, and it likely attracted prehistoric birds, which made 15 percent of the tracks.

Additionally, the warm, wet paleoclimate received up to 70 inches of precipitation annually. “The samples we analyzed indicate it was roughly equivalent to modern-day Miami,” Fiorillo adds in the statement.

The research was focused at and near the Nanushuk Formation, an outcrop of sedimentary rock between 94 million and 113 million years old—which, crucially, formed around the same time as an early version of the Bering Land Bridge connecting Asia and North America.

Almost every Cretaceous Period dinosaur that eventually lived in what came to be the American Southwest crossed that land bridge, the team told High Country News’ Emily Schwing in September. Studying the prehistoric creatures’ Alaska range, they say, helps shed light on their cross-continental journey.

But some of the greatest insights from the study are the clues it offers into ancient climates.

“The tracks are interesting, but I think the more important information in the paper is that there’s a geochemical record of high rainfall and fossils of decent-sized trees,” Matthew Carrano, a research geologist and Dinosauria curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, tells Smithsonian magazine in an email.

While the polar region received varying amounts of sunlight throughout the year in the Cretaceous, similar to today, the findings show the weather was more consistently warmer and wet. How the region’s flora and fauna survived, the authors suggest in the statement, may offer clues into our climate-changing present and future, with the Arctic warming as much as four times faster than the rest of the world.

“Given that we have no similar ecosystems today, this is important because it provides us with a past window into times when increased global warmth permitted very different environments near the poles,” Carrano says.

For the team, this fossil site is a new jumping-off point for further research into the dynamics of the Cretaceous Arctic.

“I keep saying it’s like going to the candy store,” Fiorillo told High Country News. “Someone opened the door and here [the dinosaurs] are.”

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smar...et-dinosaur-hotspot-fossils-reveal-180983990/