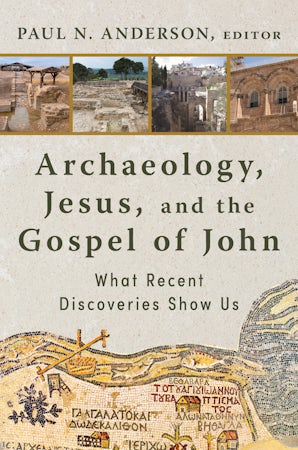

Topographical and Contextual Features

Among John’s topographical features, it is obvious that the author (1) possesses first-hand familiarity with the terrain and topography of Galilee, Samaria, and Judea. The trans-Jordan baptismal site of John the Baptist is referenced (1:28), as are the stream-waters of Aenon near Salim (3:23). Elevations are familiar, as noted by traveling “down to Capernaum” (2:12) and “up to Jerusalem” (2:13; 5:1; 11:55). Passing “through Samaria” coheres with the traveled path between Galilee and Jerusalem (4:4), and Jesus and his disciples cross over to “the other side” of the lake before coming back to Capernaum—followed also by the crowd in their boats from Tiberias (6:1, 17, 22, 24-25, 59).

(2) Aramaic and Hebrew names for places and people are translated for Greek-speaking audiences and Roman names for places are also used alongside Galilean ones. These features reflect two grounded realities. First, the original settings in which John’s tradition developed made use of Aramaic and Hebraisms; this clearly reflects the Jewish ethos of Palestine. Second, the fact that these terms are translated into Greek betrays the Gospel’s being prepared for a Hellenistic setting in the Diaspora.

(3) Jewish religious and burial customs are explained for non-Jewish audiences. The Jewish Passover was near (2:13; 6:4; 11:55); stone water jars for Jewish purification were present at the wedding (2:6); Jews did not share drinking vessels with Samaritans (4:9); the Jewish festivals of Tabernacles and Dedication and the day of preparation are mentioned (7:2; 10:22; 19:14, 42—stipulating that the season of the Dedication Festival is winter, 10:22); Sabbath expectations and regulations are referenced (5:1-18; 7:22-23; 9:16; 19:31); Jewish burial customs are noted (19:40). The author thus serves as a bridge between the Jewish ministry of Jesus and the Hellenistic setting in which the Gospel is finalized.

(4) Further, tensions between Judea and Galilee are reflected in the presentation of Jerusalem leaders rejecting the idea of Jesus’ being identified the messianic Prophet because he comes from Galilee and not the city of David (7:40-44, 52). Jesus is also accused of being a Samaritan and a demoniac by the Jerusalem leaders (8:48), and being from Nazareth is disparaged by Nathanael (1:48). These features reflect socio-religious familiarity with regional tensions and rivalries internal to Palestine, and they are especially pronounced in the rejection of the Galilean prophet by the Judean leaders.

(5) In addition, personal knowledge of people and their places of origin is represented in John’s narrative. Philip, Andrew, and Peter hail from Bethsaida (1:44; 12:20-21); Nathanael is from Cana of Galilee (21:2); Judas (son of Simon) is from Kerioth in Judea (6:71; 12:4; 13:2); the home of Mary, Martha, and Lazarus is in Bethany (11:1, 18; 12:1), Jesus is from Nazareth (1:45; 18:5, 7; 19:19); Mary of Magdala features prominently in the narrative—distinguished from others with the same name by referencing her city of origin (19:25-26; 20:1, 18); and the man named providing a tomb for Jesus is Joseph of Arimathea (19:38). Thus, many people are identified by their domestic places of origin in John, reflecting features of personal knowledge within the tradition.

Mundane Features in John

In addition to Palestinian and Jewish features of John’s narrative, a number of mundane features are unique within John’s story of Jesus. (1) Distances, directions, amounts, and costs are also known and conveyed. The middle of the lake is correctly referenced as 25 or 30 stadia (furlongs—about 5-6 kilometers; the Sea of Galilee is around 11 kilometers across; 6:19), stating how far the disciples had rowed. Bethany is said to be 15 stadia (2.5 kilometers) from Jerusalem (11:18), accounting for the presence of Jewish leaders coming from Jerusalem to grieve the loss of Lazarus.

(2) Other spatial and mundane details, which play no role in the advance of the narrative, are also referenced in John. The boat is about 100 meters from shore in John 21:8 (200 pēchōn—cubits), and Jesus instructs the disciples to cast their nets on the “right” side of the boat. The number of large fishes caught up in the net is 153 (21:11—a number not readily recognizable as having a symbolic function). The fish eaten is a prepared food common to locals (opsarion, 6:9; 21:9, 13), and the bread eaten is barley loaves (krithinou, 6:9, 13). Likewise, it is the right ear of the servant that is severed, and the perpetuator’s and the victim’s names are also given: Peter and Malchus (18:10).

(3) Measures, costs, and times of day are also featured distinctively in John’s narrative. The amount of water held in six stone jars is two or three metrētas (2:6, twenty or thirty gallons), and the weight of embalming myrrh and aloes is listed as being around 100 pounds (litras hekaton, 19:39). The cost of feeding the multitude is listed as two-thirds of a year’s wage, and the cost of the pure-nard perfume is nearly a full year’s wage (200 and 300 denarii, 6:7; 12:5—details shared with Mark’s rendering). The time of day is mentioned several times: the “tenth hour,” suggesting the end of the day (1:39); the “sixth hour,” alluding to the middle of the day (4:6; 19:14); the time of the official’s son being healed was the “seventh hour,” connected with the timing of Jesus’ word from afar (4:52-53).

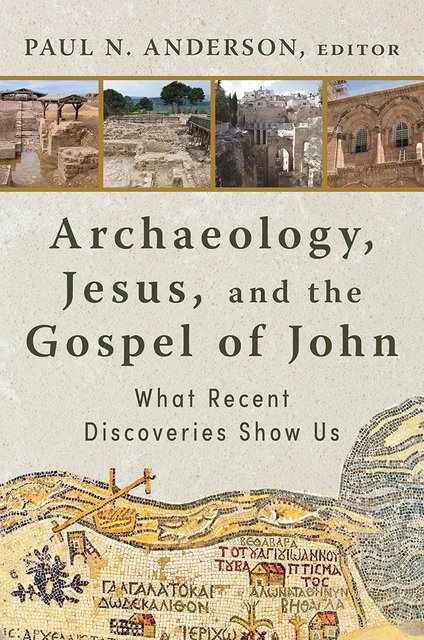

Archaeological Soundings in John

In the light of the above phenomena, John’s archaeological features are all the more impressive in terms of the realism they contribute to understanding the historical ministry of Jesus. These cohere with an important essay written by William Foxwell Albright in 1956, followed by Raymond E. Brown several years later. Along these lines, James H. Charlesworth has advanced the subject of archaeology and Jesus considerably, and the John, Jesus, and History Project invited fifteen papers on the subject at the Society of Biblical Literature meetings, which will be published in the near future.

(1) First, the Transjordan baptismal site of John the Baptist is distinctively referenced three times in John (1:28; 3:26; 10:40), which coheres with archaeological findings over the last several decades. What archaeologists have discovered at the site of Al-Maghtas is a series of pools on the path of Wadi al-Kharrar, a stream that flows into the Jordan River from the east. These pools show evidence of having served as ancient baptismal sites, perhaps going back to the time of Jesus. Established as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2015, this site is found along an ancient road crossing the Jordan River from the King’s Highway to Jerusalem. Pilgrimage records, monasteries, and hermitage dwellings abound from the 4th through the 6th centuries, and while certainty is elusive, the Johannine presentation of John baptizing across the Jordan—at least at this site—is confirmed by archaeological research.

(2) A second Johannine site attested by recent archaeological research involves the reference to the Pool of Bethesda in Jerusalem (John 5:2). The reference to five porticoes has been somewhat confusing to scholars, as construction in Greco-Roman times was rectangular, with virtually no pentagon structures. However, a reference to “the place of the twin pools” in Jerusalem has been found in the Qumran writings (Copper Scroll, Cave 3, Col. 11), and if there were indeed two side-by-side pools in Jerusalem, surrounded by four porches, with one running in between the pools, that would explain this unusual detail in the Fourth Gospel.

This site is located near the Church of St. Anne in Jerusalem, and this is the traditional site of the healing of the lame man in John 5. Archaeological evidence of its being a therapy and healing site in ancient times is confirmed by the discovery of Asclepius images in the area, so the man waiting for 38 years to be healed seems to match the function of the site. Archaeologists have also confirmed two pools with a column running between them, so the presentation of the healing by the Pool of Bethesda matches the archaeological evidence regarding such a setting.

(3) A second pool mentioned in the Gospel of John has also been corroborated by archaeological discoveries, but more recently. In John 9:1-11, Jesus healed the blind man and sent him to go and wash in the Pool of Siloam. Because the meaning of the word is translated (Siloam means “sent,” 9:7), scholars have assumed that because this reference carried symbolic meaning, it was theological in its origin rather than historical. After all, the man becomes something of an apostle (an apostle is “one who is sent,” with a commission), and this inference served as further evidence of John’s theological interest at the expense of historical concern. A small pool, fed by the Gihon Spring, was the assumed site of the pool for more than a century.

In 2004, however, things changed with the discovery of a second Pool of Siloam, a much larger one, a short distance away. As excavators sought to repair a water pipe, archaeologists discovered a series of steps leading down to a flat surface, which turned out to be a cleansing pool. Coins from the first century were found, suggesting that this site had been buried since that time. As a Mikveh, a Jewish pool of purification, this larger one was used for ritual cleansing and purification before people entered the temple in Jerusalem.

This also explains why the blind man was instructed by Jesus to wash in the pool, and why he was confronted by religious authorities in the temple area. If blindness was associated with impurity, the man’s healing required the rite of purification and official certification for him to be restored to social acceptance. In that sense, key features of the healing of the blind man in John 9 are corroborated by the discovery of the second Pool of Siloam. The healings by the pools in Jerusalem are also corroborated independently by the reference in Matthew 21:14 that Jesus performed healings on the blind and the lame people in the temple area of Jerusalem.

(4) A fourth detail in John’s story of Jesus is corroborated by the findings of recent excavations: the stone pavement (lithostrōtos, 19:13) has been found, upon which Pilate’s Praetorium was located. In Jerusalem, there are several sites where floors made of large stones are still visible. Then again, the term could also reference a tile mosaic or an elevated platform on which the judgment seat of Pilate would have stood. Either way, any of these options would fit the mention of “the Upper City” by Josephus as the place where Herod had his palace, coinciding with the area being referenced in the Gospel of John, where Gabbatha (Aramaic for “the high place” or “the ridge of the house”) identifies the place with a different name. The adding of an Aramaic name is thus not a translation. It is a different name used alongside the official Roman name for the same general settings, reflecting on-the-ground familiarity with the governing site of Pilate’s rule and its various appellatives. Thus, like the references to the two pools, this familiarity would have antedated the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 CE.

(5) A fifth feature commanding archaeological interest in the Gospel of John is the 1968 discovery of a spike driven through the heel or anklebone of a crucifixion victim in Jerusalem. The man’s name is “Jehohanan,” who was probably crucified around the time of the Roman destruction of the city in 70 CE. Josephus references 2,000 Jews being crucified in order to motivate the surrender of the city. This spike, still embedded in the heel of its victim, casts light upon three features of the Johannine crucifixion narrative.

First, it reflects the use of nails in Jerusalem crucifixions, even if the use of ropes was less costly. The Fourth Gospel alone references the use of nails in relation to the crucifixion of Jesus (20:25), and this discovery shows that John’s presentation is not simply an expansion upon a biblical text. Second, the spike, driven through the anklebone, suggests a robust means of supporting the victim’s weight, as legs were on the outsides of the wooden post, rather than feet being together. Third, the leg bone itself was fractured, reflecting crurifragium (the breaking of legs, alone mentioned in John 19:32), which helped victims die sooner.

In these and other ways, John’s presentation coheres with Roman crucifixion practices, archaeologically and historically. Despite the theological meaning attached to the piercing of the side of Jesus with a spear in 19:34-35, “fulfilling” the Scriptures of Psalm 34:20 and Zechariah 12:10 as attested by the truth-telling eyewitness, this does not mean these sorts of reports were concocted. Further, the fact that Jehohanan was given a proper burial also corroborates the desire of Jesus’ followers in John to place him in a proper tomb. The reference to the tomb offered by Joseph of Arimathea as an unused tomb in John 19:41 is also corroborated by Luke 23:53, as Luke adds to his use of Mark one of more than 70 details or features that coincide with John. Thus, the Johannine crucifixion account bears with it a good deal of independent realism, which archaeological findings corroborate.