GAZA — After weeks of protest at the Israeli border fence

peaked this week, Gazans returned to their daily lives of struggle, many wondering what, if anything, had been accomplished.

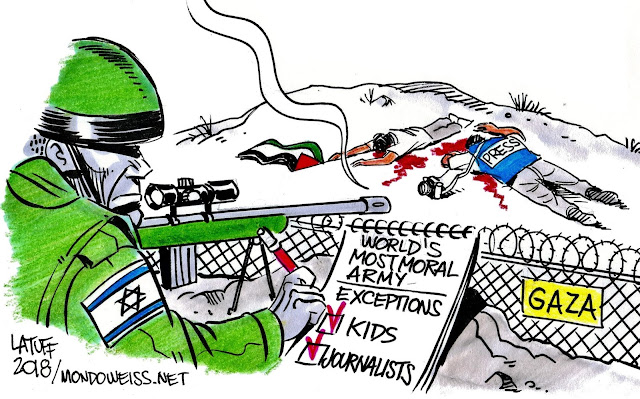

The cost was clear: Over 100 Palestinians killed by Israeli snipers, 60 of them on Monday alone, and over 3,500 wounded since the campaign began on March 30, Gaza medical officials said.

Hamas, the Islamic militant group that governs Gaza and organized the protests, did gain a victory in international messaging, with Israel widely condemned for what critics said was disproportionate use of force against mostly unarmed protesters.

In Geneva on Friday, the United Nations Human Rights Council voted overwhelmingly to censure Israel and called for an inquiry.

But to many Gazans, the tangible benefits of so much bloodshed were hard to discern, with plenty of blame to go around — including for Hamas.

At a market near the main protest camp, Abdul Rahman, 59, a vegetable trader, called the effort a total waste. “Zero,” he said. “In fact, less than zero.”

He condemned the Israelis, the Arab allies who he said had betrayed the Palestinians, and the leadership of Gaza. “We didn’t open the fence, and the blockade has not been lifted. There was only killing.”

In his sermon at noon prayers on Friday,

Ismail Haniya, the leader of Hamas, put a positive spin on the protests, called “The Great Return March,” a reference to the goal of Palestinian refugees to return to lands lost to Israel in 1948.

“We are living in the throes of victory and the beginning of the end of the humanitarian tragedy,” he proclaimed.

Mr. Haniya hailed Egypt’s rare gesture of good will toward Gaza in opening its border crossing at Rafah, on the southern edge of the territory, for the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, which began a day earlier. The opening would ease the 11-year-old blockade of Gaza, he said, adding that the border protests would continue until the blockade was entirely lifted.

But many Gazans, having lost friends or suffered grievous wounds in the protests, feel cheated by Hamas.

Eight lean young men, some still wearing bloodstained clothes, dragged away clumps of barbed wire on Thursday that protesters had torn from the fence dividing Gaza from Israel.

Selling the wire as scrap for 70 cents a kilo, they could at least salvage something from of the protests.

“Nothing achieved,” said Mohammed Haider, 23. “People are dead. They deceived us that we would breach the fence. But that didn’t happen.”

Inside Hamas, a very different debate has erupted. The harsh response of Israeli soldiers on Monday has created “strong pressure” inside the movement for a military response, said Basem Naim, a former minister of health in Gaza who now works with the Hamas international relations office. “People say ‘If we have the capacity to resort to armed resistance, why not do it?’”

But the Hamas leadership was resisting such “emotional” calls, Mr. Haim said, in recognition of the rare public relations coup that their movement, once better known for suicide attacks and rocket strikes, had attained this week.

The strains of the blockade on Gaza, which Israel and Egypt imposed, citing security reasons, have been obscured in recent years by other crises in the Middle East. Now Hamas hopes to capitalize on the widespread outrage at images of Gazans being shot by Israeli solders to pressure Israel into making some concessions.

The effort seemed to make headway Friday with the vote by the United Nations council.

“Those responsible for violations must in the end be held accountable,” Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, the head of the council, said in a

statement Friday. “What do you become when you shoot to kill someone who is unarmed, and not an immediate threat to you? You are neither brave, nor a hero.”

Israel, which considers the council biased, said in a statement by the Foreign Ministry that the council “once again has proved itself to be a body made up of a built-in, anti-Israel majority, guided by hypocrisy and absurdity.”

As the Gaza protests evolved, they had a series of shifting goals in addition to casting Israel in a negative light: breaching the fence to symbolize the return to the lost lands; challenging the blockade to ease economic distress; and, ultimately, expressing Palestinian rejection of moving the United States Embassy to Jerusalem from Tel Aviv.

Yehya Sinwar, the Hamas leader in Gaza, center, speaking to protesters last month.

Israel said the protesters were being used as cover by militants who intended to attack its soldiers and nearby communities.

To prove that point, Israeli officials pointed to a statement by a Hamas leader this week that 50 of the 60 protesters killed on Monday were members of the group.

Mr. Naim, the Hamas official, said the 50 people described were Hamas supporters as well as militants, and that all were unarmed when killed.

The Israeli military said eight armed militants were killed in a shootout with its forces at the fence during Monday’s protest.

In any event, the “great return” did not occur, given Israel’s determination to prevent any breach of the barrier. By the end of the week, the world’s attention had moved to North Korea, the latest Trump administration scandal and Britain’s royal wedding.

And Hamas is no closer to improving the lives of increasingly restless Gazans. The group lacks money to even pay public employees’ salaries or other expenses of governing.

Its plight has been deepened by the faltering reconciliation efforts with its archrival, the Fatah-dominated Palestinian Authority run by President Mahmoud Abbas in the West Bank.

Protesters burning tires on Monday near the Gaza border with Israel.

“Overall Hamas is in the same corner it was a month or two ago,” said Nathan Thrall, director of the International Crisis Group’s Israeli-Palestinian project. “It simply doesn’t have an answer about how to get out of this predicament or even how to capitalize on these protests.”

On Friday, organizers called for people to gather at the protest sites in the late afternoon. Mr. Haniya and other Hamas leaders were there. But others showed up in relatively low numbers, seemingly another measure of the waning popular appetite for the protests, which are planned to go on until the end of Ramadan in early June.

With Gaza unemployment at 43 percent and tens of thousands of employee salaries slashed by the Palestinian Authority sanctions, Egypt is encouraging a step-by-step approach to reconciliation that would see the Western-backed authority gradually take over governance of the coastal enclave.

The United Nations special coordinator for the Middle East peace process, Nickolay E. Mladenov, said the most urgent need for Gaza was to start development projects that were already approved. That would create jobs, increase access to potable water and electricity and create a more conducive atmosphere for reconciliation.

“The economy has disappeared,” he said. “Effectively, we need to revive life in Gaza.”

But after three international donor meetings in the past three months, and years of stalled projects, Mr. Mladenov said people had a right to be skeptical.

At Gaza’s main Shifa hospital, where entire floors were packed with young men recovering from gunshot wounds, many insisted they were happy to have paid such a high price. But other former protesters expressed bitter recrimination, blaming their own leaders as much as Israel.

“Our future is lost because of the Jews, and because of Hamas,” said Mahmoud Abu Omar, a 26-year-old with one arm wrapped in bandages.

He’d been shot, he said, as he aimed his slingshot across the fence. He had hoped the protests would somehow ease the frustrations of his life — his impatience to marry, to earn some money, to travel outside Gaza. They did not.