- Joined

- Dec 6, 2010

- Messages

- 33,424

- Reaction score

- 5,686

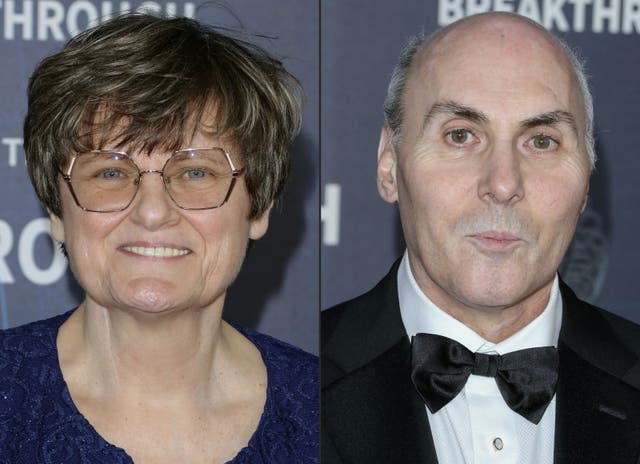

Nobel Prize for Medicine goes to Katalin Kariko and Drew Weissman, pioneers of COVID vaccine

STOCKHOLM, Oct 2 (Reuters) - Hungarian scientist Katalin Kariko and U.S. colleague Drew Weissman, who met in line for a photocopier before making mRNA molecule discoveries that paved the way for COVID-19 vaccines, won the 2023 Nobel Prize for Medicine on Monday.

"The laureates contributed to the unprecedented rate of vaccine development during one of the greatest threats to human health in modern times," the Swedish award-giving body said in the latest accolade for the pair.

The prize, among the most prestigious in the scientific world, was selected by the Nobel Assembly of Sweden's Karolinska Institute medical university and comes with 11 million Swedish crowns (about $1 million) to share between them.

Kariko, a former senior vice president and head of RNA protein replacement at German biotech firm BioNTech, is a professor at the University of Szeged in Hungary and adjunct professor at the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn).

"We are not working for any kind of reward," Kariko, who struggled for years to find grants for her research, said in remarks alongside Weissman at UPenn's Philadelphia campus, a few hours after she was awoken by the call from Stockholm. "The importance was to have a product which is helpful."

Co-winner Weissman, a professor in vaccine research also at UPenn, said it was a "lifetime dream" to win and recalled working intensely with Kariko for more than 20 years, including middle-of-the-night emails as they both suffered disturbed sleep.

In 2005, Kariko and Weissman developed so-called nucleoside base modifications, which stop the immune system from launching an inflammatory attack against lab-made mRNA, previously seen as a major hurdle against any therapeutic use of the technology.

"We couldn't get people to notice RNA as something interesting," Weissman said on Monday. "Pretty much everybody gave up on it."

MASS USE

BioNTech said in June that about 1.5 billion people across the world had received its mRNA shot, co-developed with Pfizer. It was the most widely used shot in the West.

Having grown up in a village in a house without running water or a refrigerator, Kariko got a biochemistry doctorate in Szeged before she and her husband sold their Soviet-made Lada car, sewed some cash into their daughter's teddy bear and went to the U.S. on a one-way ticket.

The daughter, Susan Francia, became a U.S. national rower and Olympic gold winner.

At UPenn, Kariko tried to turn mRNA into a treatment tool throughout the 1990s but struggled to win grants because work on DNA and gene therapy captured most of the scientific community's attention at the time.

Kariko has said she endured ridicule from university colleagues for her dogged pursuit, and her failure to secure research grants led to UPenn demoting her from a full-time professor track in 1995.

Weissman received his doctorate from Boston University in 1987 and joined UPenn in 1997.

The two have said they met and began chatting in 1998 while waiting for rationed photocopying machine time.

"Maybe you have some more copy machines now," Kariko said at UPenn on Monday. "I bragged about how I can do RNA, and Drew was interested in vaccines, and that is how our collaboration started."

Sir Andrew Pollard, an immunology professor at Oxford University who pursued a different technology when co-developing the lesser-used COVID vaccine by AstraZeneca, said it was "absolutely right that the ground-breaking work" done by Kariko and Weissman should be recognised by the Nobel committee.

PANDEMIC BREAKTHROUGH

Messenger or mRNA, discovered in 1961, is a natural molecule that serves as a recipe for the body's production of proteins. Use of lab-made mRNA to instruct human cells to make therapeutic proteins, long regarded as impossible, was commercially pioneered during the pandemic, also by Moderna.

Prospective mRNA uses include cancer therapies and vaccines against malaria, influenza and rabies.

The medicine prize kicks off this year's Nobel awards with the remaining five to be unveiled in coming days.

The prizes, first handed out in 1901, were created by Swedish dynamite inventor and wealthy businessman Alfred Nobel.

Last year's medicine prize went to Swede Svante Paabo for sequencing the genome of the Neanderthal and other past winners include Alexander Fleming, who shared the 1945 prize for the discovery of penicillin.

"If you don't enjoy what you are doing then you shouldn't do it," Kariko said on Monday. "If you want to be rich, I don't know the answer for that. But if you would like to solve problems, then science is for you."

Reporting by Niklas Pollard, Johan Ahlander in Stockholm, Ludwig Burger in Frankfurt, Krisztina Than in Budapest, Terje Solsvik in Oslo and Jonathan Allen in New York; Editing by Andrew Cawthorne.

https://www.reuters.com/business/he...icine-nobel-covid-19-vaccine-work-2023-10-02/

STOCKHOLM, Oct 2 (Reuters) - Hungarian scientist Katalin Kariko and U.S. colleague Drew Weissman, who met in line for a photocopier before making mRNA molecule discoveries that paved the way for COVID-19 vaccines, won the 2023 Nobel Prize for Medicine on Monday.

"The laureates contributed to the unprecedented rate of vaccine development during one of the greatest threats to human health in modern times," the Swedish award-giving body said in the latest accolade for the pair.

The prize, among the most prestigious in the scientific world, was selected by the Nobel Assembly of Sweden's Karolinska Institute medical university and comes with 11 million Swedish crowns (about $1 million) to share between them.

Kariko, a former senior vice president and head of RNA protein replacement at German biotech firm BioNTech, is a professor at the University of Szeged in Hungary and adjunct professor at the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn).

"We are not working for any kind of reward," Kariko, who struggled for years to find grants for her research, said in remarks alongside Weissman at UPenn's Philadelphia campus, a few hours after she was awoken by the call from Stockholm. "The importance was to have a product which is helpful."

Co-winner Weissman, a professor in vaccine research also at UPenn, said it was a "lifetime dream" to win and recalled working intensely with Kariko for more than 20 years, including middle-of-the-night emails as they both suffered disturbed sleep.

In 2005, Kariko and Weissman developed so-called nucleoside base modifications, which stop the immune system from launching an inflammatory attack against lab-made mRNA, previously seen as a major hurdle against any therapeutic use of the technology.

"We couldn't get people to notice RNA as something interesting," Weissman said on Monday. "Pretty much everybody gave up on it."

MASS USE

BioNTech said in June that about 1.5 billion people across the world had received its mRNA shot, co-developed with Pfizer. It was the most widely used shot in the West.

Having grown up in a village in a house without running water or a refrigerator, Kariko got a biochemistry doctorate in Szeged before she and her husband sold their Soviet-made Lada car, sewed some cash into their daughter's teddy bear and went to the U.S. on a one-way ticket.

The daughter, Susan Francia, became a U.S. national rower and Olympic gold winner.

At UPenn, Kariko tried to turn mRNA into a treatment tool throughout the 1990s but struggled to win grants because work on DNA and gene therapy captured most of the scientific community's attention at the time.

Kariko has said she endured ridicule from university colleagues for her dogged pursuit, and her failure to secure research grants led to UPenn demoting her from a full-time professor track in 1995.

Weissman received his doctorate from Boston University in 1987 and joined UPenn in 1997.

The two have said they met and began chatting in 1998 while waiting for rationed photocopying machine time.

"Maybe you have some more copy machines now," Kariko said at UPenn on Monday. "I bragged about how I can do RNA, and Drew was interested in vaccines, and that is how our collaboration started."

Sir Andrew Pollard, an immunology professor at Oxford University who pursued a different technology when co-developing the lesser-used COVID vaccine by AstraZeneca, said it was "absolutely right that the ground-breaking work" done by Kariko and Weissman should be recognised by the Nobel committee.

PANDEMIC BREAKTHROUGH

Messenger or mRNA, discovered in 1961, is a natural molecule that serves as a recipe for the body's production of proteins. Use of lab-made mRNA to instruct human cells to make therapeutic proteins, long regarded as impossible, was commercially pioneered during the pandemic, also by Moderna.

Prospective mRNA uses include cancer therapies and vaccines against malaria, influenza and rabies.

The medicine prize kicks off this year's Nobel awards with the remaining five to be unveiled in coming days.

The prizes, first handed out in 1901, were created by Swedish dynamite inventor and wealthy businessman Alfred Nobel.

Last year's medicine prize went to Swede Svante Paabo for sequencing the genome of the Neanderthal and other past winners include Alexander Fleming, who shared the 1945 prize for the discovery of penicillin.

"If you don't enjoy what you are doing then you shouldn't do it," Kariko said on Monday. "If you want to be rich, I don't know the answer for that. But if you would like to solve problems, then science is for you."

Reporting by Niklas Pollard, Johan Ahlander in Stockholm, Ludwig Burger in Frankfurt, Krisztina Than in Budapest, Terje Solsvik in Oslo and Jonathan Allen in New York; Editing by Andrew Cawthorne.

https://www.reuters.com/business/he...icine-nobel-covid-19-vaccine-work-2023-10-02/

Last edited:

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/KWDGJDIZ5JCFTEBZTMGQTRORQQ.jpg)