You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

What books are you reading?

- Thread starter PurpleStorm

- Start date

- Joined

- Feb 10, 2023

- Messages

- 2,306

- Reaction score

- 4,554

It is very long. I've been going forever and am only just approaching WW2.How's this book going? Any interesting information that isn't really well known to the public?

Yes it's well worth a read and highly regarded and quite fair in its assessments.

I haven't read any other biographies on him specifically, only deep dives on partial topics. It certainly has lots of information most are not aware of (I won't go in to specifics) that is away from Hollywood Hitler garbage regurgitated in documentaries.

You get a good picture of how he developed and how traits growing up were still with him later (but as I said I am only just getting to Poland) and shaped his behaviour.

A good bio if you are wanting one on the subject.

- Joined

- Dec 6, 2010

- Messages

- 3,201

- Reaction score

- 4,894

- Joined

- Jan 14, 2013

- Messages

- 39,242

- Reaction score

- 36,072

Currently reading Song of the Cell.

All of Siddhartha Mukherjee's books have been masterpieces, and this one is no different.

All of Siddhartha Mukherjee's books have been masterpieces, and this one is no different.

- Joined

- Jan 20, 2013

- Messages

- 33,274

- Reaction score

- 65,299

My daughters beat me yesterday working together, which made me proud, mainly that they were working together, but also I taught them to play and try to always teach them a bit of strategy and tactics when we play.View attachment 1037562

I may have to follow suite. My handsome son kicked my ass at the brewery recently.

I think I have a decent understanding of the fundamentals of chess but I have never bothered to memorize openings. Maybe it is time to address that.

Last night I found a chess youtuber who embraces my preferred style, namely, that the best defense is more offense, so I am going to play around with those ideas today and try them out in some games.

- Joined

- Dec 5, 2009

- Messages

- 20,638

- Reaction score

- 12,774

Empire of the Damned, by Jay Kristoff.

Enjoying it a lot so far. Loved the first book, and this is going well too. Tried a previous book of his, and it was way too edgy, and cringey for me, so I am glad I gave him another shot.

Enjoying it a lot so far. Loved the first book, and this is going well too. Tried a previous book of his, and it was way too edgy, and cringey for me, so I am glad I gave him another shot.

Close to finishing up the book Electric Universe. Over the years I've read mentions that there are possibly many mistakes with how we believe the universe operates. So I thought I'd finally see what these people were talking about. Interesting book.

Amazon product ASIN B007SP1LK8

The last 150 years have seen immense progress in understanding electrical phenomena, and we are seeing voluminous evidence of plasma and magnetic fields (always caused by electric currents) in space. Nevertheless, the conventional cosmology taught today remains essentially a theory based solely on gravity and nuclear fusion. The Electric Universe introduces the universe that many in mainstream science ignore, and authors Wallace Thornhill and David Talbott offer a sweeping critique of today’s popular cosmology. They show that galaxies, stars (including our Sun), and comets can be best understood through the well-tested behavior of electricity—the one force about which astronomers seem to know almost nothing, a force that is 1036 or more times as strong as gravity. Compelling, highly readable, and superbly illustrated, this book provides a comprehensive introduction to what will surely be the beginnings of a scientific revolution in the years ahead. The Electric Universe understanding eliminates the need for the highly imaginative, sensational yet logic-breaking constructs of black holes, dark matter and energy, and replaces them with laboratory demonstrated plasma phenomena.

The Electric Universe

Amazon product ASIN B007SP1LK8

The last 150 years have seen immense progress in understanding electrical phenomena, and we are seeing voluminous evidence of plasma and magnetic fields (always caused by electric currents) in space. Nevertheless, the conventional cosmology taught today remains essentially a theory based solely on gravity and nuclear fusion. The Electric Universe introduces the universe that many in mainstream science ignore, and authors Wallace Thornhill and David Talbott offer a sweeping critique of today’s popular cosmology. They show that galaxies, stars (including our Sun), and comets can be best understood through the well-tested behavior of electricity—the one force about which astronomers seem to know almost nothing, a force that is 1036 or more times as strong as gravity. Compelling, highly readable, and superbly illustrated, this book provides a comprehensive introduction to what will surely be the beginnings of a scientific revolution in the years ahead. The Electric Universe understanding eliminates the need for the highly imaginative, sensational yet logic-breaking constructs of black holes, dark matter and energy, and replaces them with laboratory demonstrated plasma phenomena.

- Joined

- Aug 23, 2015

- Messages

- 18,568

- Reaction score

- 9,010

- Joined

- Oct 26, 2008

- Messages

- 4,326

- Reaction score

- 4,068

intriguing, will check it out. Nice cheery reading there LOLCurrently reading Molly. She killed herself. Her husband wrote the book about her and their relationship. Was recommended by a pal.

View attachment 1037593

- Joined

- Aug 23, 2015

- Messages

- 18,568

- Reaction score

- 9,010

I don’t do cherry reading lol.intriguing, will check it out. Nice cheery reading there LOL

- Joined

- Jun 24, 2006

- Messages

- 46,732

- Reaction score

- 36,416

Sounds like a real riotCurrently reading Molly. She killed herself. Her husband wrote the book about her and their relationship. Was recommended by a pal.

View attachment 1037593

- Joined

- May 19, 2014

- Messages

- 7,422

- Reaction score

- 1,090

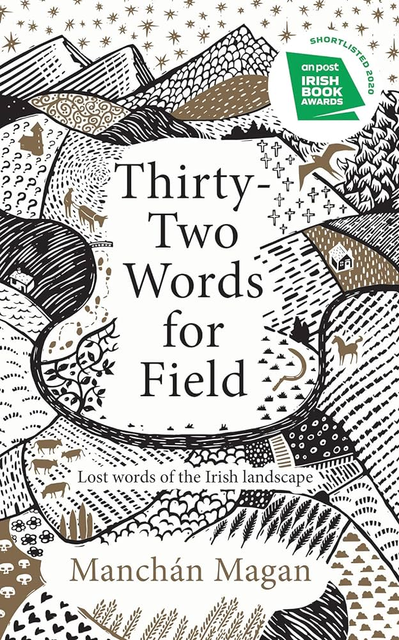

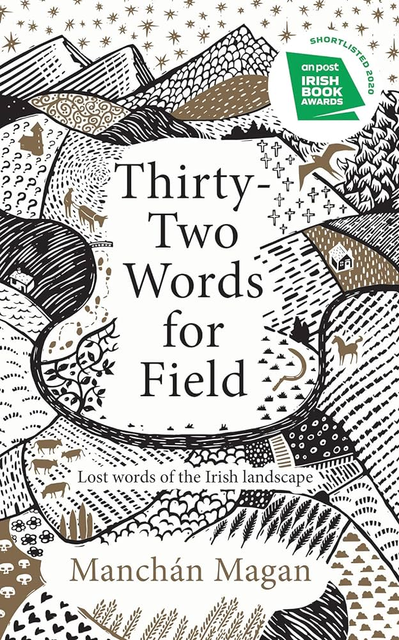

Recently finished Thirty Two Words for Field: Lost Words of the Irish Landscape by Manchán Magan

I really wanted to love this book. However, while I can appreciate a lot of what Magan has to say, overall it was just a bit too light and ‘wish-washy’ for me. The book sets out to provide an exploration of the Irish language and the layers of myth and “ancient knowledge” supposedly encoded within it. Some aspects were good. Magan really brings out the beauty and lyricism of the language and draws on some interesting folklore.

The general sense that important aspects of the Irish language are fading as it ceases to be a living one is very poignant. Or rather, ceases to fulfil the same function as the language of daily life and culture in its traditional rural communities. Even though the language will survive, with new non-native speakers it will inevitably be changed. Words lose their multiplicity of meanings, as well as older mythological associations, in favour of more purely functional ones. This book is important at least in drawing attention to what is being lost and categorising older words and meanings. The intersection he explores between language, folklore, and environmentalism can be interesting too.

However, Magan frequently loses the run of himself completely and the book is riddled with numerous historical, anthropological and linguistic errors right the way through. The claims he makes are frequently unverifiable and entirely unsourced. He wants to paint Irish culture, as filtered through the language, as somehow more indigenous than other European cultures. He draws comparison to Australian Aboriginals at a few points, comparisons which strike me as incredibly far-fetched. He also makes some absolutely insane leaps of logic regarding Irish and its relation to Arabic and Sanskrit, even including an encounter with a Hindu mystic in a Himalayan cave which, I must say, sounds completely made up.

Much of his core idea is that Irish somehow provides a more profound understanding of life and human nature than more commonly-spoken languages, such as English, do. This kind of linguistic relativism is extremely contentious amongst experts in this field, but Magan throws around these concepts with reckless abandon. All-in-all, I found he lost my interest more and more as the book went on and I started losing patience with the approach. Interesting in some respects, but fundamentally flawed in many areas.

I really wanted to love this book. However, while I can appreciate a lot of what Magan has to say, overall it was just a bit too light and ‘wish-washy’ for me. The book sets out to provide an exploration of the Irish language and the layers of myth and “ancient knowledge” supposedly encoded within it. Some aspects were good. Magan really brings out the beauty and lyricism of the language and draws on some interesting folklore.

The general sense that important aspects of the Irish language are fading as it ceases to be a living one is very poignant. Or rather, ceases to fulfil the same function as the language of daily life and culture in its traditional rural communities. Even though the language will survive, with new non-native speakers it will inevitably be changed. Words lose their multiplicity of meanings, as well as older mythological associations, in favour of more purely functional ones. This book is important at least in drawing attention to what is being lost and categorising older words and meanings. The intersection he explores between language, folklore, and environmentalism can be interesting too.

However, Magan frequently loses the run of himself completely and the book is riddled with numerous historical, anthropological and linguistic errors right the way through. The claims he makes are frequently unverifiable and entirely unsourced. He wants to paint Irish culture, as filtered through the language, as somehow more indigenous than other European cultures. He draws comparison to Australian Aboriginals at a few points, comparisons which strike me as incredibly far-fetched. He also makes some absolutely insane leaps of logic regarding Irish and its relation to Arabic and Sanskrit, even including an encounter with a Hindu mystic in a Himalayan cave which, I must say, sounds completely made up.

Much of his core idea is that Irish somehow provides a more profound understanding of life and human nature than more commonly-spoken languages, such as English, do. This kind of linguistic relativism is extremely contentious amongst experts in this field, but Magan throws around these concepts with reckless abandon. All-in-all, I found he lost my interest more and more as the book went on and I started losing patience with the approach. Interesting in some respects, but fundamentally flawed in many areas.

- Joined

- Dec 28, 2022

- Messages

- 2,909

- Reaction score

- 10,425

Books? Aren't they just used to prop up computer monitors? Maybe I should read up about them. Do they come in pairs or you have to buy a bunch?Here’s a few I’m reading:

Life by Keith Richards. Rambling stories from the riff meister.

God’s Promises for Every Day by Thomas Nelson. Indexed to look up what to do if you’re feeling anxious, bored, angry, jealous etc.

Batman Year One by Frank Miller. Classic graphic novel.

Reggae Roots by Kevin O’Brian Chang & Wayne Chen. Origins of reggae music told by Jamaicans.

What are you reading?

Never read 1984, but bought that recently to read. Look forward to it.

- Joined

- Oct 13, 2008

- Messages

- 55,233

- Reaction score

- 43,786

At present:

Walking the Amazon - Ed Stafford

Lonely Planet Central Asia

Walking the Amazon - Ed Stafford

Lonely Planet Central Asia

- Joined

- Jun 24, 2006

- Messages

- 46,732

- Reaction score

- 36,416

I have like two of those I picked up at a used book store a while back. One of them was actually pretty good.Currently rereading all the ravenloft novels but kinda stuck on Tapestry of Dark Souls, kinda ran out of ambition for a bit but I'll pick it back up soon

- Joined

- Jan 2, 2015

- Messages

- 17,171

- Reaction score

- 14,158

Just picked up Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber, currently finishing The In-Between which was written by a hospice nurse. Also got bunch of Terry Pratchet waiting and I'll probably jump back into The Silmarillion at some point when I feel like chewing glass again.

- Joined

- Nov 14, 2018

- Messages

- 27,361

- Reaction score

- 42,951

Ernst Jungner storm of steel

One of 2 must reads conserning WW1 along with all quiet on western front(even if its fiction) and oh boy these books are completely from different planets

Remarques book is anti- war while jungners is almost pro war, jungner was a militarist nationalist who considered war natural and necessary for advancement of humankind

Over course of book he rises from average soldier to war hero, some people online says book is inhumanely cold and unemotional and author definetly doesnt pay much attention to deaths of people around him, at one point they execute POWs due to lack of resources to imprison them and author simply says "they were fighters,they understand"

At the same time you can only respect what a badass author is, he pulls off some heavy stuff on constant basis (He fought entire war and was wounded like 14 times)

One comment on youtube put difference between remarque and jungner well

All quiet is an average person fighting in a war "war is horrible, people suffer"

Storm of steel is story of natural born warrior who not only likes war but is very good at it "I shattered soldiers skull with a shovel and feel nothing"

I found book interesting since soldiers liking war is a bit taboo subject in society

One of 2 must reads conserning WW1 along with all quiet on western front(even if its fiction) and oh boy these books are completely from different planets

Remarques book is anti- war while jungners is almost pro war, jungner was a militarist nationalist who considered war natural and necessary for advancement of humankind

Over course of book he rises from average soldier to war hero, some people online says book is inhumanely cold and unemotional and author definetly doesnt pay much attention to deaths of people around him, at one point they execute POWs due to lack of resources to imprison them and author simply says "they were fighters,they understand"

At the same time you can only respect what a badass author is, he pulls off some heavy stuff on constant basis (He fought entire war and was wounded like 14 times)

One comment on youtube put difference between remarque and jungner well

All quiet is an average person fighting in a war "war is horrible, people suffer"

Storm of steel is story of natural born warrior who not only likes war but is very good at it "I shattered soldiers skull with a shovel and feel nothing"

I found book interesting since soldiers liking war is a bit taboo subject in society