- Joined

- Jan 1, 2020

- Messages

- 2,733

- Reaction score

- 1,700

TL;DR: Export Controls To Crush CCP High Tech Ambitions

I'm not sure how to make this more concise but there will be a lot of supplemental graphics, so you may as well skim the thread and gain some insight since you bothered to click on it. I personally feel this should've been done years ago regardless and advocated for at least as much. Given how the CCP's initial handling undoubtedly allowed the outbreak to spiral completely out of control, it would seem particularly justified in the aftermath.

The Chinese government implements a top-down, state-directed strategy of intransigent policies, acts and practices which both deliberately and indirectly undercut American output, competitiveness, investment, research, development, innovation and strategic domestically spawned industries which serve as invaluable sources of high wage employment, global exports, sustained economic growth and national security. As found by virtually every bipartisan commission and panel ever assembled.

http://www.ipcommission.org

2011 USITC Report (PDF) /2016 USTR Report (PDF) / 2017 USTR Report (PDF)

I've never been a fan of the Trump Administration's blunt use of tariffs but the instant blocks on FDI have been most welcome and these are not market based transactions anyway. The organic form of Foreign Direct Investment - such as with countries like Canada, UK, Germany - is ordinarily a great thing and means capital investment that results in a lot of stateside American job creation.

OTOH the CCP's idea of "foreign direct investment" is just code for buying up US tech assets, transferring intellectual property overseas and having American employees train their Chinese replacements. Even buying a minority stake gives you access to industrial trade secrets and every single one of the potential rejected Chinese buyers has been connected to the CCP government in one way or another. So yeah, hmm, fuck that.

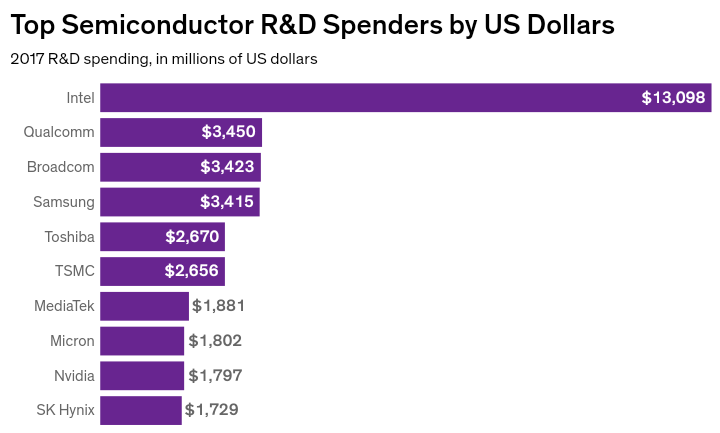

This is at the core of America's global technological supremacy. To date, the US remains cutting edge in virtually all segments (µP, µC, SoC, GPU, AIC) and it's one of the few industries that never moved the bulk of its production offshore. Aerospace is another notable there, for many of the same reasons including higher IP protection, military applications and national security. Yeah, Broadcom has since re-relocated to the US.

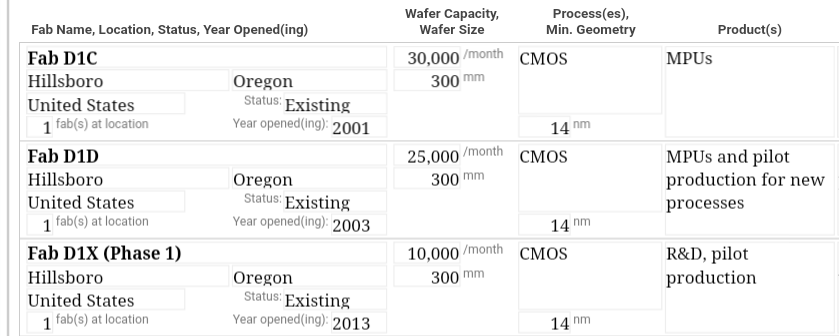

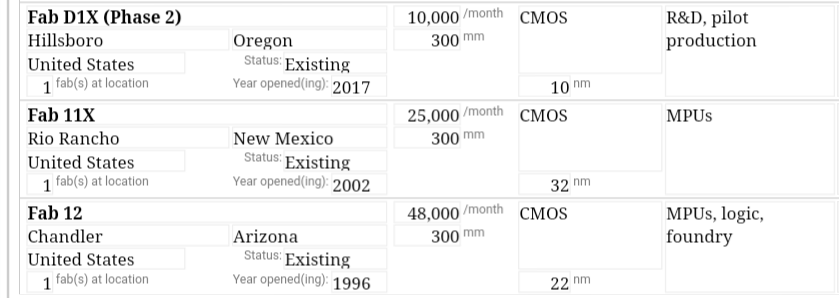

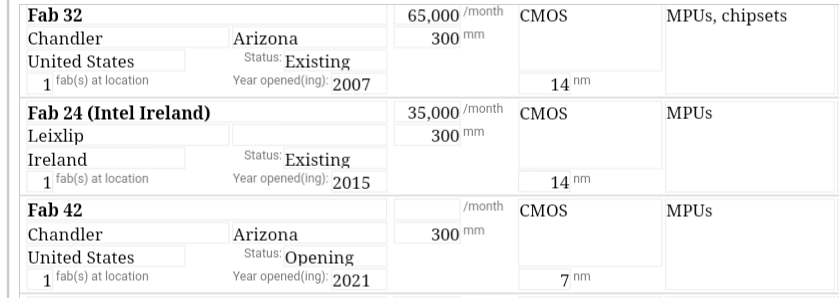

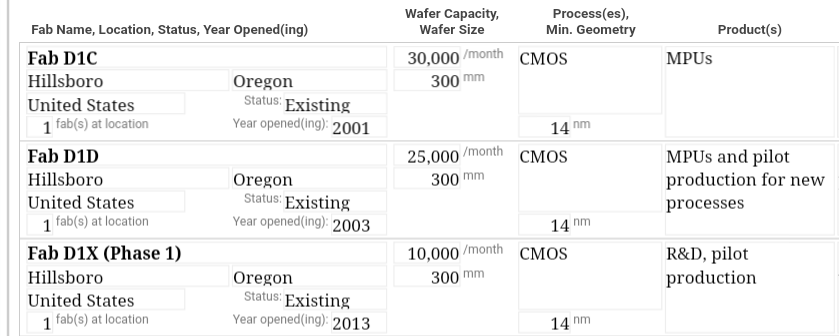

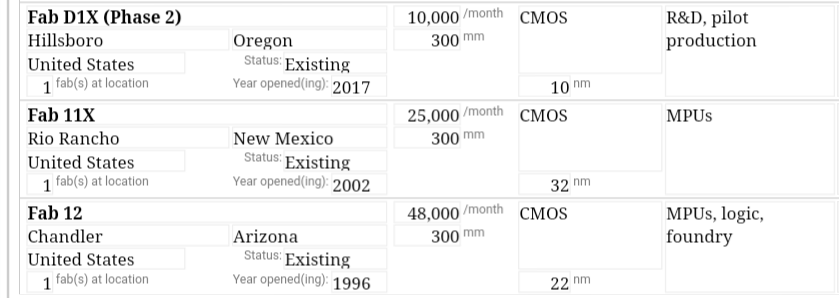

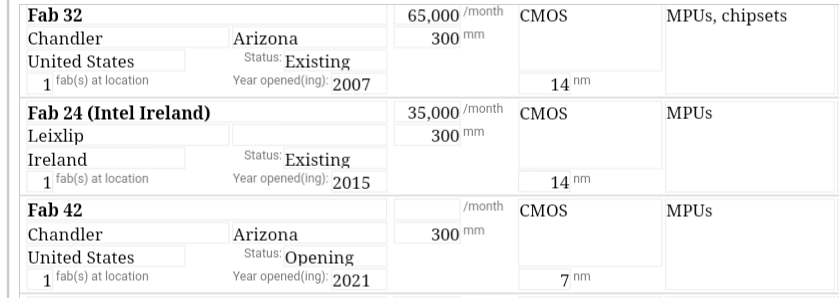

Example: A glimpse into Intel's manufacturing operations.

Why Can't China Make Semiconductors?

In other words, China is quite keenly aware of how condensed matter physics as explained by the laws of quantum and statistical mechanics 'work' at the fundamental level. Yet they've still not been able mount a domestic semiconductor industry - which was literally brought into existence by the United States - for the engineering and manufacturing of cutting edge integrated circuits. They've already been failing at it for decades now. Amusing, but have made (read: stole) notable strides in the last five years.

If you want to set China's ambitions back for at least another couple decades, it wouldn't make a whole lot of sense to deny them chips from Intel, Qualcomm, Micron, Microchip, Texas Instruments, NVIDIA, et al. when such a significant portion of US semiconductor revenue is made through Chinese sales (and they can't do without them). Rather, you place export controls on the chipmaker's suppliers and choke off all access to the materials, machinery, equipment, software and services they require to raise their own industry and which can't be acquired anywhere else to any appreciable degree.

Namely these firms in particular. One of them is based in the Netherlands (ASML) and the other Japan obviously. This is where it would be nice to utilize relationships with geopolitcal allies rather than throwing them under the bus.

How do we know export controls are effective?

America's Assault On China's Tech Ambitions

It's not just their budding SC firms that can be crushed.

China's second largest manufacturer of telecom equipment and the number four smartphone maker in the United States, ZTE, is on its way to shutting down after the US government banned the company from doing business with American component suppliers, including chipmakers Qualcomm and Intel Corp., both of which it relied heavily on for parts used its smartphones. The company's future may now depend on an appeal to modify or reverse the 7-year ban.

The news was revealed in a press release which noted that, "the major operating activities of the company have ceased". ZTE's English-language homepage has also been stripped of much of its content, including its online store, apparently signifying that the company's days are numbered, at least in Western markets.

ZTE was inexplicably bailed out. Oh Hey, Look.

(HiSilicon isn't there yet, doesn't meet all of Huawei's product demand and is fabless to boot. They're dependent on TSMC for manufacturing. The US protects Taiwan in part because it's home to some of the largest pure play semiconductor foundries and most advanced process technology in the world with assets heavily integrated into the US defense network and supply chain. It kind of adds a layer of context to the relationship, and would be certain war if the mainland ever attempted taking that island.)

And, of course.

I'm not sure how to make this more concise but there will be a lot of supplemental graphics, so you may as well skim the thread and gain some insight since you bothered to click on it. I personally feel this should've been done years ago regardless and advocated for at least as much. Given how the CCP's initial handling undoubtedly allowed the outbreak to spiral completely out of control, it would seem particularly justified in the aftermath.

The Chinese government implements a top-down, state-directed strategy of intransigent policies, acts and practices which both deliberately and indirectly undercut American output, competitiveness, investment, research, development, innovation and strategic domestically spawned industries which serve as invaluable sources of high wage employment, global exports, sustained economic growth and national security. As found by virtually every bipartisan commission and panel ever assembled.

http://www.ipcommission.org

2011 USITC Report (PDF) /2016 USTR Report (PDF) / 2017 USTR Report (PDF)

I've never been a fan of the Trump Administration's blunt use of tariffs but the instant blocks on FDI have been most welcome and these are not market based transactions anyway. The organic form of Foreign Direct Investment - such as with countries like Canada, UK, Germany - is ordinarily a great thing and means capital investment that results in a lot of stateside American job creation.

OTOH the CCP's idea of "foreign direct investment" is just code for buying up US tech assets, transferring intellectual property overseas and having American employees train their Chinese replacements. Even buying a minority stake gives you access to industrial trade secrets and every single one of the potential rejected Chinese buyers has been connected to the CCP government in one way or another. So yeah, hmm, fuck that.

This is at the core of America's global technological supremacy. To date, the US remains cutting edge in virtually all segments (µP, µC, SoC, GPU, AIC) and it's one of the few industries that never moved the bulk of its production offshore. Aerospace is another notable there, for many of the same reasons including higher IP protection, military applications and national security. Yeah, Broadcom has since re-relocated to the US.

Example: A glimpse into Intel's manufacturing operations.

Why Can't China Make Semiconductors?

Almost from the start, central planning proved to be a serious impediment. Early government ideas included importing secondhand Japanese semiconductor lines that were outdated before they were even shipped. Expensive efforts to build a domestic industry from scratch in the 1990s faltered due to bureaucracy, delays and a lack of customers for the kind of chips China was making.

Another weakness was a lack of capital. For decades, labor-intensive industries -- such as assembling mobile phones -- were the route to riches in China, attracting investment from entrepreneurs and bureaucrats alike. Making semiconductors, by contrast, requires billions in up-front capital and can take a decade or more to see a return. In 2016, Intel Corp. alone spent $12.7 billion on R&D. Few if any Chinese companies have that capacity or the experience to make such an investment rationally. And central planners typically resist that kind of risky and far-sighted spending.

China seems to recognize this problem. Since 2000, it has shifted away from subsidizing semiconductor research and production, and toward making equity investments, in the hope that market forces could play a larger role. Yet funds continue to be misallocated: Over the past 18 months, there's been a spate of government-juiced overinvestment in semiconductor plants, many of which lack sufficient technology. Those that eventually open will likely contribute to a glut in memory chips, spelling financial trouble for the domestic industry.

But perhaps the biggest long-term challenge for China is technology acquisition. Though the government would like to develop an industry from the ground up, its best efforts are still one or two generations behind the U.S. A logical solution would be to buy technology from American companies or form partnerships with them. That's the route taken by cutting-edge firms in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

Yet China can't do the same. Its efforts to purchase American semiconductor companies (often at huge premiums) are regularly blocked for security reasons. Japan, South Korea and Taiwan have put Chinese acquisitions under similar scrutiny. By one accounting, China has made $34 billion in bids for U.S. semiconductor companies alone since 2015, yet completed only $4.4 billion in deals globally in that span.

In other words, China is quite keenly aware of how condensed matter physics as explained by the laws of quantum and statistical mechanics 'work' at the fundamental level. Yet they've still not been able mount a domestic semiconductor industry - which was literally brought into existence by the United States - for the engineering and manufacturing of cutting edge integrated circuits. They've already been failing at it for decades now. Amusing, but have made (read: stole) notable strides in the last five years.

If you want to set China's ambitions back for at least another couple decades, it wouldn't make a whole lot of sense to deny them chips from Intel, Qualcomm, Micron, Microchip, Texas Instruments, NVIDIA, et al. when such a significant portion of US semiconductor revenue is made through Chinese sales (and they can't do without them). Rather, you place export controls on the chipmaker's suppliers and choke off all access to the materials, machinery, equipment, software and services they require to raise their own industry and which can't be acquired anywhere else to any appreciable degree.

Namely these firms in particular. One of them is based in the Netherlands (ASML) and the other Japan obviously. This is where it would be nice to utilize relationships with geopolitcal allies rather than throwing them under the bus.

How do we know export controls are effective?

America's Assault On China's Tech Ambitions

For a sense of the damage the United States can inflict on China with export controls, take a trip to the city of Jinjiang on the country’s southeastern coast.

That’s where Fujian Jinhua Integrated Circuit Co. built a $6 billion plant to produce semiconductors as part of China’s goal of making the country a self-sufficient technology powerhouse. But after the U.S. President barred exports to the company, its dream is now in tatters with consultants from American suppliers gone, the factories silent and workers rattled.

Less than a month ago, Jinhua was full-speed ahead on an enormous undertaking financed by the local government that blanketed its corner of the city with bristling power plants, hulking workers’ dormitories and modern research labs. It was within months of a deadline to kick off full-scale production of some 60,000 wafers a month, a key step to giving China a competitive producer of memory chips used in smartphones.

Then the U.S. Justice Department accused it of stealing American technology, and Commerce slammed the door on purchases of the chipmaking gear it needed to hit that milestone. Expansion work halted as its American and even European suppliers skipped town. Now, uncertainty shrouds a company President Xi Jinping’s touted as one of three future domestic champions of chipmaking.

The day the U.S. announced its ban, Applied Materials Inc. staff packed up and left, according to people familiar with the matter. The American company had shipped components to Jinhua as recently as Sept. 20, according to an airway bill seen by Bloomberg. KLA-Tencor Corp and Lam Research Corp. also recalled their engineers, the people said. Even Dutch giant ASML Holding N.V. -- whose EUV machines are the linchpin in next-generation chipmaking -- pulled out within days, abandoning work on a second assembly line. The once-smooth influx of equipment ground to a halt. On a windy afternoon in November, a giant plot of land adjoining Jinhua’s campus earmarked for its second facility stood vacant, not even a bulldozer in sight.

So rapid was the exodus that, in many cases, Jinhua employees had no inkling of the departures till they were gone, one person said. Only a smattering of the foreign-employed engineers bothered to inform their peers before catching flights to Shanghai and Taipei, the person said. “They didn’t even give us time to say goodbye,” one person said.

From a broader perspective, the speed with which the U.S. squashed Jinhua’s ambitions underscores the extent to which China -- despite well-publicized intentions of becoming a global tech superpower by 2025 -- remains reliant on American innovation. Jinhua was to spearhead the transition for a country beholden to giants from Intel Corp. to Micron Technologies Inc. It’s an effort that’s become critical as the rivalry between the world’s two largest economies deepens. Indeed, It was Micron that first accused Jinhua and UMC of purloining its trade secrets, setting events in motion.

“Memory chips are cement for the entire IT industry, so China is eager to break the international monopoly and improve its own power of discourse in the world,” said Roger Sheng, an industry analyst with Gartner Research.

Jinhua was a key cog in a campaign to move away from chip imports -- an influx that surpasses China’s annual spending on oil. Now that vision’s in jeopardy. To some, it seems a matter of time until the Trump administration targets the other two designated national champions: Tsinghua Unigroup’s Yangtze River Memory and Hefei Changxin, run by the government of central Anhui province.

It's not just their budding SC firms that can be crushed.

China's second largest manufacturer of telecom equipment and the number four smartphone maker in the United States, ZTE, is on its way to shutting down after the US government banned the company from doing business with American component suppliers, including chipmakers Qualcomm and Intel Corp., both of which it relied heavily on for parts used its smartphones. The company's future may now depend on an appeal to modify or reverse the 7-year ban.

The news was revealed in a press release which noted that, "the major operating activities of the company have ceased". ZTE's English-language homepage has also been stripped of much of its content, including its online store, apparently signifying that the company's days are numbered, at least in Western markets.

ZTE was inexplicably bailed out. Oh Hey, Look.

(HiSilicon isn't there yet, doesn't meet all of Huawei's product demand and is fabless to boot. They're dependent on TSMC for manufacturing. The US protects Taiwan in part because it's home to some of the largest pure play semiconductor foundries and most advanced process technology in the world with assets heavily integrated into the US defense network and supply chain. It kind of adds a layer of context to the relationship, and would be certain war if the mainland ever attempted taking that island.)

And, of course.