- Joined

- Aug 11, 2012

- Messages

- 3,523

- Reaction score

- 1,974

Just wait until the super rats turn up.

wow, thats like baby beaver level size.

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

Just wait until the super rats turn up.

A California deer mouse captured in Inaja Memorial Park this month tested positive for hantavirus, a potentially deadly virus with no vaccine or cure, the county’s communications office said.

Probably has to do with the fires, no?

Southwest, why is there a mice problem in the Southwest? Can't the city of San Diego control the mice population? Why doesn't the rest of the country have this problem?

Reservoir and Reservoir Distributions: United States

All hantaviruses known to cause hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) are carried by New World rats and mice of the family Muridae, subfamily Sigmodontinae. The subfamily Sigmodontinae contains at least 430 species, which are widespread in North and South America. The rodent hosts of HPS are generally not associated with urban environments, although some species, including the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus), and white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus), will enter human habitation in rural and suburban areas.

Several hantaviruses that are pathogenic for humans have been identified in the United States. In general, each virus has a single primary rodent host. Other small mammals can be infected as well but are much less likely to transmit the virus to other animals or humans. The deer mouse is the host for Sin Nombre virus (SNV), the primary causative agent of HPS in the United States. The deer mouse is common and widespread in rural areas throughout much of the United States. Although prevalence varies temporally and geographically, on average about 10% of deer mice tested throughout the range of the species show evidence of infection with SNV.

Other hantaviruses associated with sigmodontine rodents and known to cause HPS include New York virus, which is hosted by the white-footed mouse; Black Creek Canal virus, which is hosted by the cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus); and Bayou virus, which is hosted by the rice rat (Oryzomys palustris). Nearly the entire continental United States falls within the range of one or more of these host species. Several other sigmodontine rodent species in the United States are associated with additional hantaviruses that have yet to be implicated in human disease.

Recent studies have confirmed that infected deer mice are present in every habitat type-from desert to alpine tundra, although the prevalence of infection is higher in certain middle-altitude habitats. Surveys of rodents throughout the United States suggest that SNV is distributed in all locations where P. maniculatus is found. Related hantaviruses are also found throughout the geographic range of their rodent carriers. Given that P. maniculatus and P. leucopus are commonly found in the peridomestic setting and typically have higher population densities than other rodents, cases of HPS can be expected to occur throughout the range of these rodent species. Other implicated species, such as S. hispidus and O. palustris, generally do not live in such close proximity to human habitats, and this factor may decrease the probability of human exposure to viruses shed by these rodents.

Lower population density, a lesser propensity for peridomestic encroachment and a narrower geographic and ecologic distribution (and perhaps differing virulence) may explain the lack of human disease associated with hantaviruses (or genetic sequences thought to represent additional hantaviruses) from meadow and California voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus and californicus, respectively), the western harvest mouse (Reithrodontomys megalotis), and the brush mouse (Peromyscus boylii).

New York City is a place where rats climb out of toilets, bite babies in their cribs, crawl on sleeping commuters, take over a Taco Bell restaurant, and drag an entire slice of pizza down the subway stairs. So as Matthew Combs puts it, “Rats in New York, where is there a better place to study them?”

Combs is a graduate student at Fordham University and, like many young people, he came to New York to follow his dreams. His dreams just happened to be studying urban rats. For the past two years, Combs and his colleagues have been trapping and sequencing the DNA of brown rats in Manhattan, producing the most comprehensive genetic portrait yet of the city’s most dominant rodent population.

As a whole, Manhattan’s rats are genetically most similar to those from Western Europe, especially Great Britain and France. They most likely came on ships in the mid-18th century, when New York was still a British colony. Combs was surprised to find Manhattan’s rats so homogenous in origin. New York has been the center of so much trade and immigration, yet the descendants of these Western European rats have held on.

When Combs looked closer, distinct rat subpopulations emerged. Manhattan has two genetically distinguishable groups of rats: the uptown rats and the downtown rats, separated by the geographic barrier that is midtown. It’s not that midtown is rat-free—such a notion is inconceivable—but the commercial district lacks the household trash (aka food) and backyards (aka shelter) that rats like. Since rats tend to move only a few blocks in their lifetimes, the uptown rats and downtown rats don’t mix much.

When the researchers drilled down even deeper, they found that different neighborhoods have their own distinct rats. “If you gave us a rat, we could tell whether it came from the West Village or the East Village,” says Combs. “They’re actually unique little rat neighborhoods.” And the boundaries of rat neighborhoods can fit surprisingly well with human ones.

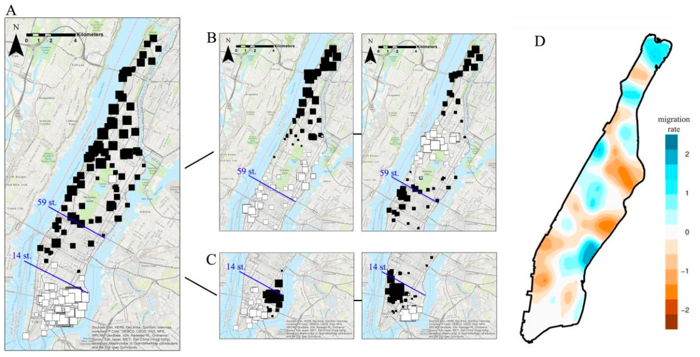

Left: a map showing two clusters of rats uptown (black, north of 59th Street) and downtown (white, south of 14 Street). Right: a map showing estimated migration rates of rats.

Combs and a team of undergraduate students spent their summers trapping rats—beginning in Inwood at the north tip of Manhattan and working their way south. They got permission from the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, which gave them access to big green spaces like Central Park as well as medians and triangles and little gardens that dot the city. And they asked local residents. “More often than not, they were very, very happy to show us exactly where they had rats.” says Combs. A crowdsourced map of rat sightings also proved very helpful.

Rats, although abundant, are not easily fooled into traps. They’re wary of new objects. To entice them, the bait was a potent combination of peanut butter, bacon, and oats. And the team placed their traps near places where rats had clearly crawled. They looked for rat holes, droppings, chew marks on trash cans, and sebum marks—aka the grease tracks rats leave when they traverse the same path to the garbage over and over again.

For the DNA analysis, Combs cut off an inch or so of the rats’ tails. (Over 200 of these tails are still saved in vials in a lab freezer.) The team also took tissue samples for other researchers interested in studying how rats spread diseases through the urban environment. And some of the rats they skinned and stuffed for the collections of the Yale University Peabody Museum of Natural History, where they will join stuffed rats from 100 years ago.

Combs is now writing his dissertation on the ecology of New York’s rats. He’s looking at how a number of characteristics—natural features like parks, social factors like poverty, physical infrastructure like the subway system—account for the spatial distributions of rats in Manhattan.

The point of all this, ultimately, is to help New York manage its rat problem, which is annoying as well as a genuine public-health hazard due to rat-borne diseases. In July, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio announced a $32 million war plan against the varmints. The New York Times noted wryly that when it came to rats, “There have been 109 mayors of New York and, it seems, nearly as many mayoral plans to snuff out the scourge. Their collective record is approximately 0-108.”

It's just as bad in Chicago. I can't walk through my alley at night without hearing several of them scatter.

I once saw a rat the size of a kangaroo in Chicago.

True story.

Exaggerated a little.

On topic I saw the biggest fucking rat ever in New Orleans, I thought it was a cat.

- San Diego (+12)