- Joined

- Mar 21, 2007

- Messages

- 12,119

- Reaction score

- 7,317

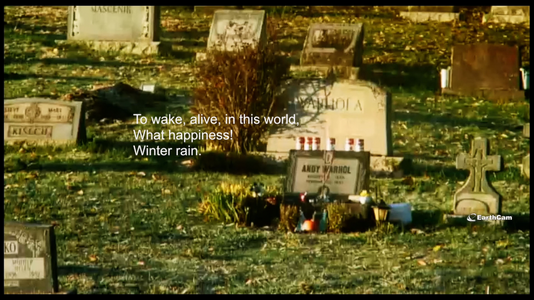

Tommaso (USA/Italy, 2019)

A loose, semi-autobiographical film from Abel Ferrara, Tommaso follows its titular character (Willem Dafoe), an aging American filmmaker living in Rome, as he struggles with sobriety, domestic life, and creative stagnation.

Tommaso’s daily routine consists of Italian lessons, teaching acting classes, 12-step meetings, and long, meandering walks through the city. On the surface, his life appears stable, but beneath it lies a constant undercurrent of jealousy, self-doubt, and quiet desperation. He is a man perpetually teetering on the edge—calm for a moment, then suddenly swept up in paranoia and rage. At home, he plays the devoted husband and father, yet he is consumed by his inability to control his relationship. He fears infidelity, though his own thoughts and actions are steeped in flirtation and sexual fantasy. At his core, Tommaso is a self-destructive addict—one whose slightest frustration threatens to trigger an eruption of anger. Whether he is self destructive because he is an addict or if he became an addict due to being self destructive is an existential question that must remain unanswered. He longs for control but remains incapable of controlling himself.

Dafoe delivers a deeply committed performance, capturing Tommaso’s inner turmoil with a blend of quiet introspection and volatile emotion. His presence anchors the film, elevating scenes that might otherwise feel like aimless improvisation.

Ferrara adopts a stripped-down, cinema verite style, giving the film the raw feel of an observational documentary rather than a traditional narrative. Rome, often romanticized in cinema, is instead presented in an almost mundane light, reinforcing the film’s grounded, unvarnished aesthetic. While this approach adds realism, it also contributes to the film’s languid pacing, which at times borders on tedious.

Ferrara blurs the lines between reality, memory, and hallucination, but the dreamlike structure feels muddled. As the film reaches its conclusion, it becomes difficult to discern what is real and what is imagined. Clearly, this is intentional—Ferrara wants the audience to inhabit Tommaso’s fractured perspective—but the effect is more frustrating than illuminating.

For all its moments of raw honesty, Tommaso never fully justifies its self-indulgence. Viewers who connect with its introspective, freeform storytelling may find it hypnotic. Others, like myself, will remain on the outside looking in, observing a vaguely interesting but ultimately meandering story that never fully resonates.

Rating: 5/10

A loose, semi-autobiographical film from Abel Ferrara, Tommaso follows its titular character (Willem Dafoe), an aging American filmmaker living in Rome, as he struggles with sobriety, domestic life, and creative stagnation.

Tommaso’s daily routine consists of Italian lessons, teaching acting classes, 12-step meetings, and long, meandering walks through the city. On the surface, his life appears stable, but beneath it lies a constant undercurrent of jealousy, self-doubt, and quiet desperation. He is a man perpetually teetering on the edge—calm for a moment, then suddenly swept up in paranoia and rage. At home, he plays the devoted husband and father, yet he is consumed by his inability to control his relationship. He fears infidelity, though his own thoughts and actions are steeped in flirtation and sexual fantasy. At his core, Tommaso is a self-destructive addict—one whose slightest frustration threatens to trigger an eruption of anger. Whether he is self destructive because he is an addict or if he became an addict due to being self destructive is an existential question that must remain unanswered. He longs for control but remains incapable of controlling himself.

Dafoe delivers a deeply committed performance, capturing Tommaso’s inner turmoil with a blend of quiet introspection and volatile emotion. His presence anchors the film, elevating scenes that might otherwise feel like aimless improvisation.

Ferrara adopts a stripped-down, cinema verite style, giving the film the raw feel of an observational documentary rather than a traditional narrative. Rome, often romanticized in cinema, is instead presented in an almost mundane light, reinforcing the film’s grounded, unvarnished aesthetic. While this approach adds realism, it also contributes to the film’s languid pacing, which at times borders on tedious.

Ferrara blurs the lines between reality, memory, and hallucination, but the dreamlike structure feels muddled. As the film reaches its conclusion, it becomes difficult to discern what is real and what is imagined. Clearly, this is intentional—Ferrara wants the audience to inhabit Tommaso’s fractured perspective—but the effect is more frustrating than illuminating.

For all its moments of raw honesty, Tommaso never fully justifies its self-indulgence. Viewers who connect with its introspective, freeform storytelling may find it hypnotic. Others, like myself, will remain on the outside looking in, observing a vaguely interesting but ultimately meandering story that never fully resonates.

Rating: 5/10