- Joined

- Apr 27, 2015

- Messages

- 810

- Reaction score

- 723

The UFC’s Featherweight division has proven one of the tallest mountains in all of combat sports. Dating back to its inception, the belt has been held by nothing but all time greats, won only by fighters among the very best in MMA. Ilia Topuria recently added his name to that legendary pantheon by knocking out Alexander Volkanovski, but it was his first defense that truly solidified him as the division’s king.

Max Holloway is the man who made Alexander Volkanovski’s crown, picking up the Featherweight title after Jose Aldo’s lengthy reign and Conor McGregor’s brief interlude. Holloway was unable to defeat Volkanovski during their three fight series despite a close effort in the second fight that could have easily swung his way. But many thought Holloway could present Topuria issues that an ageing Volkanovski failed to, his otherworldly durability and volume testing the power-punching champion’s motor, heart, and ability to adjust in a way we haven’t yet seen.

And for two rounds, Holloway did just that, giving as good as he got, pushing Topuria to his limit, and bringing out the best in him. It was shaping up to be one of the best fights I’d ever seen, but then it was time for Topuria to shut the lights out.

In all of MMA, there’s no fighter more difficult to beat by simply landing the big shot than Max Holloway. He’s taken the best shots from hitters like Jose Aldo, Dustin Poirier, and Calvan Kattar only to ask for more, seemingly disappointed that they couldn’t crack even harder. Durability is a young man’s shield and once it goes, it rarely comes back. But although the greatest chin in the sport had been tested more as of late, Justin Gaethje even dropping Holloway in his last fight, it still held up. Banking on a finish against Max Holloway would be foolish.

But Ilia Topuria isn’t the average monstrous puncher. He isn’t even the average puncher among the elite, instead appearing in a league of his own. He transfers weight into picture perfect power shots in a way few else do in MMA, but he’s just as good at putting himself in position to land those punches, creating the conditions necessary to deliver his power. Against Volkanovski, Topuria proved that he could maximize the impact of his power and make excellent decisions around when to deliver it. Against Josh Emmett, he proved he could box patiently when smashing wasn’t the path of least resistance. But against Max Holloway, Topuria wove the two together, using the subtleties of his boxing skillset to keep himself safe, limit Holloway’s volume, and keep the score close, while picking choice moments to sit down on howitzers and make them count.

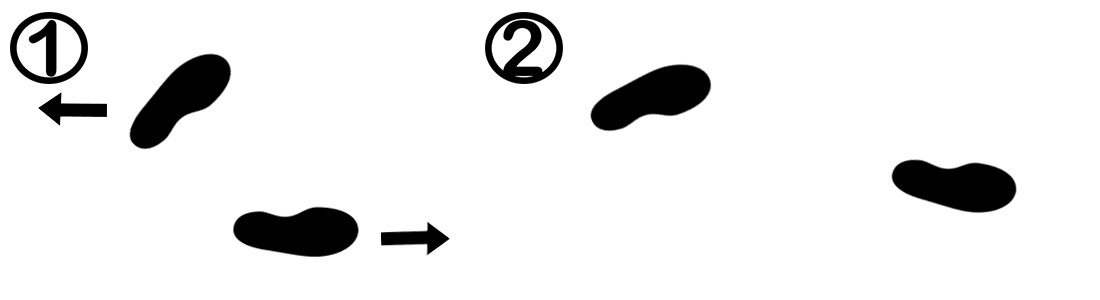

To understand Topuria’s style, we first have to start with his stance, for much of his success comes from his ability to maintain it under fire and play with his positioning within it. Topuria shifts his weight around a lot, but he approached Holloway mainly from a rear-foot heavy, bladed stance with a slight fold in his rear hip.

It resembles a classic boxing stance, wherein the rear weight distribution provides some extra distance to see punches coming, and the natural hip fold affords a measure of proactive defense. His lead leg is kept light, allowing him to feint and step with the foot without fully committing his weight. As a result, he was often able to see Holloway’s intercepting strikes coming and pull back or avoid pressing onto them.

Topuria had the arduous task of facing Holloway as the shorter fighter, meaning he would have to close distance to land his strikes on one of MMA’s best long-range operators. He had a number of tactics that got him through the gap safely, but it started with his consistent and shrewd use of feints.

His feints were both varied and convincing, looking identical to his real entries. Constant foot feints with his light lead leg sold half-committed steps into range, and he would at times fully weight the leg while shifting weight onto his lead foot to provoke a bigger reaction. Body jabs paired with level changes, while slight weight transfers from rear foot to front foot sold his right hand. Topuria’s feints not only had Holloway hitting air trying to time intercepting strikes, but they allowed him to keep the pressure up without forcing a pace he couldn’t maintain. When Holloway would find some space and circle off, Topuria would follow and get right back on him with the feints, scarcely giving him room to breathe.

Like many of Holloway’s opponents, Topuria invested in calf kicks early and often. Holloway is tricky in that his broad style leaves openings to leg kicks, but it’s proved difficult to take advantage of. His outward-facing lead foot generally keeps his leg stable even when punted hard, and his long lead hand is always ready to lurch forward with a jab or lead hook to punish kickers. He also just seems to have extraordinary durability in his legs, able to absorb repeated clean connections without looking worse for wear.

Still, for a shorter fighter like Topuria, getting some kind of kicking offense going was critical in staying competitive at all ranges against the longer Holloway.

There was a battle going on between Topuria’s rear leg and Holloway’s lead hand. But while Holloway got his counters in, Topuria generally gave better than he got here. His rear foot heavy stance left him lots of room to step in and transfer weight into powerful kicks, and his constant feints hid his weight transfers into the kick fairly well, often delaying Holloway’s counter until it was too late.

Early on, Topuria looked to close distance behind level change feints and his jab, putting his right hand behind them once he’d entered range. While he found success with it, Holloway started getting the read on his entries and timing the weight transfer on his right hand:

Holloway would see the jabs and level changes signalling the entry, then back up slightly and counter with his lead hook. As Topuria transferred weight from rear foot to front foot on his right hand, his hips and shoulders open, letting Holloway’s lead hook slot in and killing his entry while Holloway circled off.

But this is where the flexibility of Topuria’s stance came into play. He had to get close in order to land his best weapons, and spending the whole fight crowding Holloway is not only dangerous, but entails fighting at a pace nobody aside from Holloway himself can sustain. Every time he took that initial step in, he gave Holloway another data point to process and work out how to keep him outside his ideal range. But he made sure the data he did give Holloway was varied and full of noise.

Topuria would played with his weight distribution, shifting weight periodically onto his lead foot and folding over his lead hip. Every shift from rear foot to front foot sold the threat of a right hand or leg kick, and repeating the motion helped dull Holloway’s response to that threat.

Where the double jabs into right hands started getting predictable, Topuria began entering into range with his weight loaded on the front foot more often, surprising Holloway with a quick lead hook or right hand.

Being able to smoothly adjust his weight within his stance also proved invaluable for Topuria defensively. An issue with rear foot heavy stances in MMA is that it can often lead to getting stuck on the rear hip. MMA fighters tend to use giving ground as their first and most comfortable layer of defense, and with the weight already loaded at the back of the stance, there isn’t much room left to pull. But Topuria rarely found himself stuck in one place. When he was caught on the back foot he would simply fold more deeply over his rear hip, underneath punches, and being able to use both hips seamlessly took him safely inside and outside of Holloway’s jab.

A big part of Holloway’s success against Justin Gaethje came from using his jab to poke and prod, prompting a big defensive motion that took Gaethje out of position and opened him up to harder strikes. But Topuria’s varied hip movement made it difficult for Holloway to predict where his head would be next, and his positioning remained intact with each movement, allowing him to transition to the next without getting stuck in one place.

The most reliable tool Topuria had for closing distance proved to be a simple rear hand lead, without any preceding strikes. The trick here is that it was hidden by all his feints and hip movement. Every time he folded over his lead hip or jutted forward in a false entry, Holloway grew a bit more desensitized and the rear hand became easier to land.

Topuria would subtly advance behind short foot feints. Then he’d step forward as if to feint once more, only to let his lead foot drift further in, widening his stance and speeding up the motion halfway through as he launched into the right hand. Holloway would stay in place and stare at what he saw as yet another feint until it was too late. The rhythm change was key to making this work consistently - Topuria’s initial step appears almost lazy, but it lulls Holloway while getting him close enough to turn up the speed when it’s too late for a proper reaction.

The downsides of leading with the rear hand so often are obvious, but they were heavily mitigated by Topuria’s subtlety in disguising it. But the advantage is that the distance is taken all in one motion. Holloway excels at using his jab and lead hook to intercept and turn an opponent’s attempted entry into his own opportunity. They need to jab at least once to fill the space between them, then Holloway slots his counter in as they take the next step, and follows them with a swarming combination as they exit. But when Topuria was able to trick him into reacting late to the right hand, there was no such easy pattern to pick up on the counter.

Leading with his rear hand allowed Topuria to take large distances and back Holloway up to the cage where he could do much of his best work, even hitting a takedown off it in the first round. But he also used it as a combination starter, surprising Holloway with the quick right and smacking him with power shots as he backed up or circled out. Wrestle-boxers throwing overhands from outside the pocket is perhaps the most quintessentially MMA strike there is, but what was remarkable about Topuria’s use is how well he maintained his positioning.

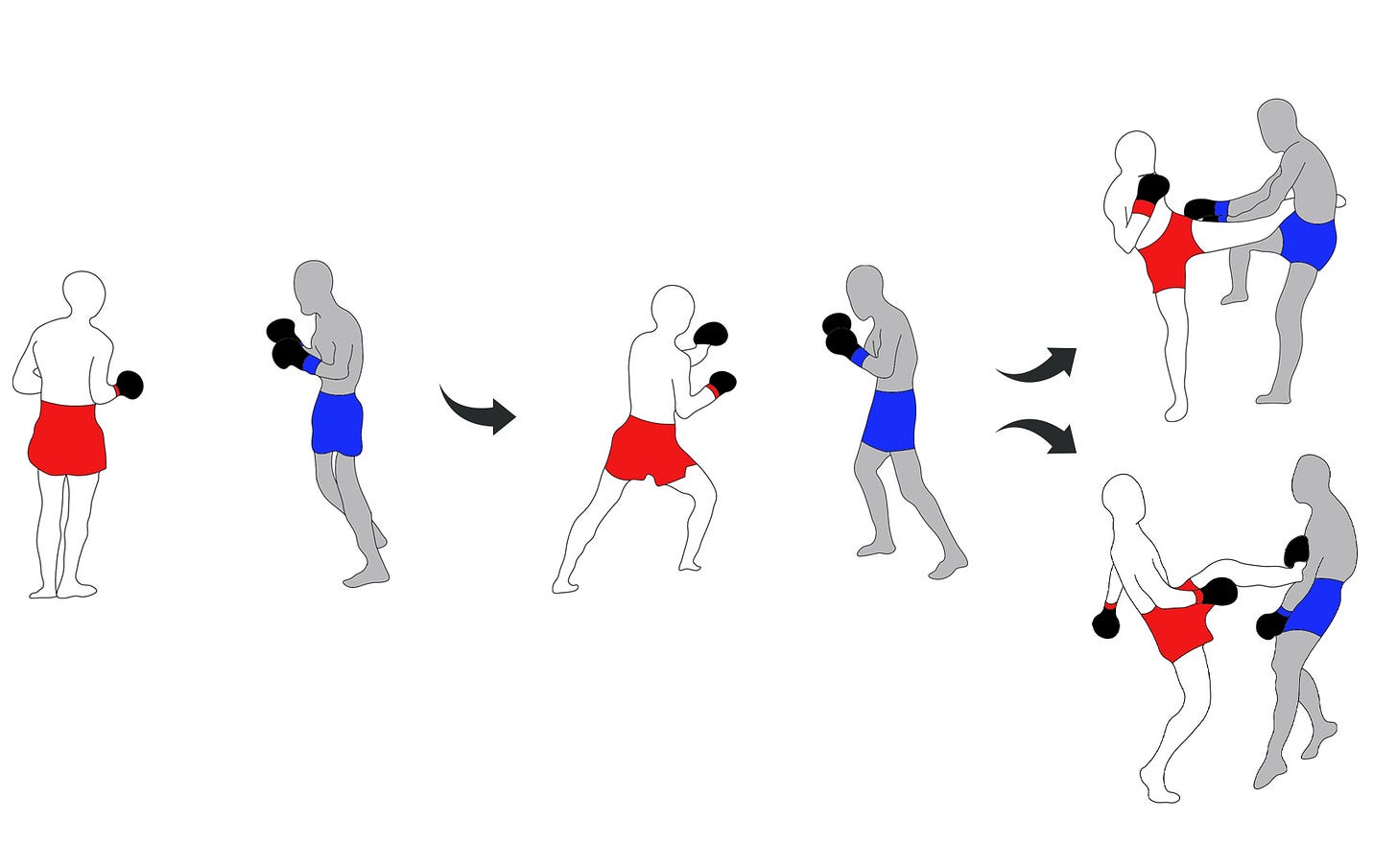

Let’s look at a similar example from Holloway’s fight with Gaethje as a reference:

Gaethje feints with his lead hand, but his step in is fairly predicable and gives Holloway a good idea of what is coming at him. Gaethje’s overhand falls just short, his momentum taking his weight past his lead foot. With his stance lost, he drifts forward and collapses into Holloway’s knee, bouncing off it like a stunned Looney Tunes character.

Now lets see how Topuria improves on it:

Topuria launches a committed right hand from outside the pocket. But instead of falling into it, he skips forward just as his weight is about to drift past his lead foot. He goes from strong stance to strong stance, quickly taking even more distance on Holloway and landing in position to transfer his weight into a strong lead hook. Holloway is caught with his own positioning broken down, trying to bail on the exchange but left surprised by Topuria’s rapid closing of distance. Note also how Topuria expects Holloway’s counter hook and keeps his right arm extended in front of his chin to block it, just lovely stuff all around.

Hopping in off a long rear hand is a tactic commonly seen in Kickboxing and Muay Thai. It’s often favored by upright kickers who use long range punches to set up their kicks. Since the weight needs to be kept relatively centered to kick effectively, overcommitting to the rear hand kills the positioning necessary to follow it up with a kick. Instead, the rear hand is usually kept light, without heavy weight transfer, and the hop in closes distance for a more powerful kick or knee.

Two of the finest strikers you’ll see in Giorgio Petrosyan and Saenchai make frequent use of this skipping straight to close distance into knees, but you’ll also see it employed by Israel Adesanya in the Octagon.

I was amazed by many aspects of Topuria’s performance. But to my eye, the most impressive feat may have been his ability to integrate the smooth hip movements and weight transfers of a power-punching boxer with the weightless distance closing footwork typical of experienced strikers in kicking sports. We’ve seen him box brilliantly before, but we haven’t seen him needing to close so much distance against a tall, lanky opponent like Holloway. Strong pocket boxers with active hip movement often struggle with mobile opponents in the large, open MMA cages, as the committed weight transfers can give opponents an escape route. Not only was Topuria more than prepared, but his approach to closing distance was uniquely subtle and something I haven’t quite seen from a puncher like him in MMA.

Max Holloway is the man who made Alexander Volkanovski’s crown, picking up the Featherweight title after Jose Aldo’s lengthy reign and Conor McGregor’s brief interlude. Holloway was unable to defeat Volkanovski during their three fight series despite a close effort in the second fight that could have easily swung his way. But many thought Holloway could present Topuria issues that an ageing Volkanovski failed to, his otherworldly durability and volume testing the power-punching champion’s motor, heart, and ability to adjust in a way we haven’t yet seen.

And for two rounds, Holloway did just that, giving as good as he got, pushing Topuria to his limit, and bringing out the best in him. It was shaping up to be one of the best fights I’d ever seen, but then it was time for Topuria to shut the lights out.

In all of MMA, there’s no fighter more difficult to beat by simply landing the big shot than Max Holloway. He’s taken the best shots from hitters like Jose Aldo, Dustin Poirier, and Calvan Kattar only to ask for more, seemingly disappointed that they couldn’t crack even harder. Durability is a young man’s shield and once it goes, it rarely comes back. But although the greatest chin in the sport had been tested more as of late, Justin Gaethje even dropping Holloway in his last fight, it still held up. Banking on a finish against Max Holloway would be foolish.

But Ilia Topuria isn’t the average monstrous puncher. He isn’t even the average puncher among the elite, instead appearing in a league of his own. He transfers weight into picture perfect power shots in a way few else do in MMA, but he’s just as good at putting himself in position to land those punches, creating the conditions necessary to deliver his power. Against Volkanovski, Topuria proved that he could maximize the impact of his power and make excellent decisions around when to deliver it. Against Josh Emmett, he proved he could box patiently when smashing wasn’t the path of least resistance. But against Max Holloway, Topuria wove the two together, using the subtleties of his boxing skillset to keep himself safe, limit Holloway’s volume, and keep the score close, while picking choice moments to sit down on howitzers and make them count.

To understand Topuria’s style, we first have to start with his stance, for much of his success comes from his ability to maintain it under fire and play with his positioning within it. Topuria shifts his weight around a lot, but he approached Holloway mainly from a rear-foot heavy, bladed stance with a slight fold in his rear hip.

It resembles a classic boxing stance, wherein the rear weight distribution provides some extra distance to see punches coming, and the natural hip fold affords a measure of proactive defense. His lead leg is kept light, allowing him to feint and step with the foot without fully committing his weight. As a result, he was often able to see Holloway’s intercepting strikes coming and pull back or avoid pressing onto them.

Topuria had the arduous task of facing Holloway as the shorter fighter, meaning he would have to close distance to land his strikes on one of MMA’s best long-range operators. He had a number of tactics that got him through the gap safely, but it started with his consistent and shrewd use of feints.

His feints were both varied and convincing, looking identical to his real entries. Constant foot feints with his light lead leg sold half-committed steps into range, and he would at times fully weight the leg while shifting weight onto his lead foot to provoke a bigger reaction. Body jabs paired with level changes, while slight weight transfers from rear foot to front foot sold his right hand. Topuria’s feints not only had Holloway hitting air trying to time intercepting strikes, but they allowed him to keep the pressure up without forcing a pace he couldn’t maintain. When Holloway would find some space and circle off, Topuria would follow and get right back on him with the feints, scarcely giving him room to breathe.

Like many of Holloway’s opponents, Topuria invested in calf kicks early and often. Holloway is tricky in that his broad style leaves openings to leg kicks, but it’s proved difficult to take advantage of. His outward-facing lead foot generally keeps his leg stable even when punted hard, and his long lead hand is always ready to lurch forward with a jab or lead hook to punish kickers. He also just seems to have extraordinary durability in his legs, able to absorb repeated clean connections without looking worse for wear.

Still, for a shorter fighter like Topuria, getting some kind of kicking offense going was critical in staying competitive at all ranges against the longer Holloway.

There was a battle going on between Topuria’s rear leg and Holloway’s lead hand. But while Holloway got his counters in, Topuria generally gave better than he got here. His rear foot heavy stance left him lots of room to step in and transfer weight into powerful kicks, and his constant feints hid his weight transfers into the kick fairly well, often delaying Holloway’s counter until it was too late.

Early on, Topuria looked to close distance behind level change feints and his jab, putting his right hand behind them once he’d entered range. While he found success with it, Holloway started getting the read on his entries and timing the weight transfer on his right hand:

Holloway would see the jabs and level changes signalling the entry, then back up slightly and counter with his lead hook. As Topuria transferred weight from rear foot to front foot on his right hand, his hips and shoulders open, letting Holloway’s lead hook slot in and killing his entry while Holloway circled off.

But this is where the flexibility of Topuria’s stance came into play. He had to get close in order to land his best weapons, and spending the whole fight crowding Holloway is not only dangerous, but entails fighting at a pace nobody aside from Holloway himself can sustain. Every time he took that initial step in, he gave Holloway another data point to process and work out how to keep him outside his ideal range. But he made sure the data he did give Holloway was varied and full of noise.

Topuria would played with his weight distribution, shifting weight periodically onto his lead foot and folding over his lead hip. Every shift from rear foot to front foot sold the threat of a right hand or leg kick, and repeating the motion helped dull Holloway’s response to that threat.

Where the double jabs into right hands started getting predictable, Topuria began entering into range with his weight loaded on the front foot more often, surprising Holloway with a quick lead hook or right hand.

Being able to smoothly adjust his weight within his stance also proved invaluable for Topuria defensively. An issue with rear foot heavy stances in MMA is that it can often lead to getting stuck on the rear hip. MMA fighters tend to use giving ground as their first and most comfortable layer of defense, and with the weight already loaded at the back of the stance, there isn’t much room left to pull. But Topuria rarely found himself stuck in one place. When he was caught on the back foot he would simply fold more deeply over his rear hip, underneath punches, and being able to use both hips seamlessly took him safely inside and outside of Holloway’s jab.

A big part of Holloway’s success against Justin Gaethje came from using his jab to poke and prod, prompting a big defensive motion that took Gaethje out of position and opened him up to harder strikes. But Topuria’s varied hip movement made it difficult for Holloway to predict where his head would be next, and his positioning remained intact with each movement, allowing him to transition to the next without getting stuck in one place.

The most reliable tool Topuria had for closing distance proved to be a simple rear hand lead, without any preceding strikes. The trick here is that it was hidden by all his feints and hip movement. Every time he folded over his lead hip or jutted forward in a false entry, Holloway grew a bit more desensitized and the rear hand became easier to land.

Topuria would subtly advance behind short foot feints. Then he’d step forward as if to feint once more, only to let his lead foot drift further in, widening his stance and speeding up the motion halfway through as he launched into the right hand. Holloway would stay in place and stare at what he saw as yet another feint until it was too late. The rhythm change was key to making this work consistently - Topuria’s initial step appears almost lazy, but it lulls Holloway while getting him close enough to turn up the speed when it’s too late for a proper reaction.

The downsides of leading with the rear hand so often are obvious, but they were heavily mitigated by Topuria’s subtlety in disguising it. But the advantage is that the distance is taken all in one motion. Holloway excels at using his jab and lead hook to intercept and turn an opponent’s attempted entry into his own opportunity. They need to jab at least once to fill the space between them, then Holloway slots his counter in as they take the next step, and follows them with a swarming combination as they exit. But when Topuria was able to trick him into reacting late to the right hand, there was no such easy pattern to pick up on the counter.

Leading with his rear hand allowed Topuria to take large distances and back Holloway up to the cage where he could do much of his best work, even hitting a takedown off it in the first round. But he also used it as a combination starter, surprising Holloway with the quick right and smacking him with power shots as he backed up or circled out. Wrestle-boxers throwing overhands from outside the pocket is perhaps the most quintessentially MMA strike there is, but what was remarkable about Topuria’s use is how well he maintained his positioning.

Let’s look at a similar example from Holloway’s fight with Gaethje as a reference:

Gaethje feints with his lead hand, but his step in is fairly predicable and gives Holloway a good idea of what is coming at him. Gaethje’s overhand falls just short, his momentum taking his weight past his lead foot. With his stance lost, he drifts forward and collapses into Holloway’s knee, bouncing off it like a stunned Looney Tunes character.

Now lets see how Topuria improves on it:

Topuria launches a committed right hand from outside the pocket. But instead of falling into it, he skips forward just as his weight is about to drift past his lead foot. He goes from strong stance to strong stance, quickly taking even more distance on Holloway and landing in position to transfer his weight into a strong lead hook. Holloway is caught with his own positioning broken down, trying to bail on the exchange but left surprised by Topuria’s rapid closing of distance. Note also how Topuria expects Holloway’s counter hook and keeps his right arm extended in front of his chin to block it, just lovely stuff all around.

Hopping in off a long rear hand is a tactic commonly seen in Kickboxing and Muay Thai. It’s often favored by upright kickers who use long range punches to set up their kicks. Since the weight needs to be kept relatively centered to kick effectively, overcommitting to the rear hand kills the positioning necessary to follow it up with a kick. Instead, the rear hand is usually kept light, without heavy weight transfer, and the hop in closes distance for a more powerful kick or knee.

Two of the finest strikers you’ll see in Giorgio Petrosyan and Saenchai make frequent use of this skipping straight to close distance into knees, but you’ll also see it employed by Israel Adesanya in the Octagon.

I was amazed by many aspects of Topuria’s performance. But to my eye, the most impressive feat may have been his ability to integrate the smooth hip movements and weight transfers of a power-punching boxer with the weightless distance closing footwork typical of experienced strikers in kicking sports. We’ve seen him box brilliantly before, but we haven’t seen him needing to close so much distance against a tall, lanky opponent like Holloway. Strong pocket boxers with active hip movement often struggle with mobile opponents in the large, open MMA cages, as the committed weight transfers can give opponents an escape route. Not only was Topuria more than prepared, but his approach to closing distance was uniquely subtle and something I haven’t quite seen from a puncher like him in MMA.