- Joined

- Jan 17, 2010

- Messages

- 13,005

- Reaction score

- 15,917

- I think i can assume we've all seen the demonization of manual laborers on social media. People look down on the man responsoble for them having a hoof over their head. I also assumer thats was common to us ol., more mature gentleman, to have constructed a tree house and a rolimã in the or childreenhood, a dog house here and there. Now it's pretty clear those type of things are a activities of the past, i observe that my nephew never owned a set of tools. Besides his uncle of course.

To the average, dumb, soap opera watching person, lying a seet of bricks and concreting is seen as a unskiled job. But those of us that have tried to lift a wall or a fence, know how much work goes in lifting one that can stay up for years.

Construction Fluctuates Cyclically, With No Secular Trend

Construction follows a somewhat different pattern. Construction employment is highly cyclical following patterns in the housing market, following the ups and downs in the business cycle, but it has little clear secular trend. In 2016, 4.7 percent of the workforce was employed in construction (6.7 million workers), with the figure heading upward over the course of the year. This is down from the 5.2 percent figure for 1970, but not out of line with the average for that decade.

The National Trend in Mining Jobs

Mining employment has largely followed the path of world energy prices as the bulk of employment in the sector is energy-related. Employment in the sector rose through the 1970s and peaked in 1982 at 1.2 percent of total employment. The collapse in world energy prices sent employment in the sector sharply lower in the next two decades, with employment in mining falling to just 0.4 percent of total employment in 1998. Higher energy prices and the fracking boom increased mining employment from 2003 until 2014. Since then, the plunge in energy prices sharply reduced employment, so it again stands at just 0.4 percent of total employment, with 626,000 total jobs in the sector.

- Lou Ferrigno and Arnold were proud brick layers

If the supply of workers interested in working in blue-collar jobs was growing as rapidly as demand, we would not have a problem. But in reality, the supply of workers for blue-collar jobs has been shrinking. People with a college degree are very unlikely to end up working in a blue-collar job, partly due to the stigma attached to manual labor. This is especially true in a tight labor market like the one the US is currently experiencing. The number of people in the labor force without a college degree could be used as a rough proxy of potential labor supply for blue-collar jobs. But as shown in the previous blog, this group of workers has been shrinking in recent years and will likely shrink even more rapidly in the coming decade.

Why is the supply of workers interested in blue-collar jobs shrinking?

https://cepr.net/publications/the-decline-of-blue-collar-jobs-in-graphs/

https://www.conference-board.org/re...ollar-Labor-Markets-Tighter-Than-White-Collar

Less educated Americans are much more likely not to be in the labor force due to disability.

The increasing share of more educated people in the US labor force is not just because the US population is becoming more educated. It is also because more non-college graduates are leaving the labor force due to disability. The increase in disability rates, partly because of the opioid epidemic, are much more concentrated in the population without a college degree and is therefore having a larger impact on the supply of workers to blue-collar and low-paid service occupations.

To be continued:

- Troght mankind history, construction workers have been the important fundantion of the developing of nations. Butr have them always bee looked down?Throughout the long history of technology and employment debates, blue-collar jobs have been widely predicted to be one of the biggest losers to technological change. Blue-collar jobs are commonly defined as those requiring significant manual labour, often involving mechanical skills to operate machines, but the term has acquired several connotations over time, including a worker's social-economic status, level of training and qualifications, and types of work (see Wickman, 2012). Blue-collar work, therefore, varies from unskilled manual tasks requiring no formal education to highly skilled and trade qualified ones (Mittal et al., 2019; Rayner, 2018). They include production (e.g., machine operators), craft (e.g., trade occupations), repair (e.g., maintenance occupations) and cleaning (e.g., labourer) occupations. In this respect, Wroblewski (2019) divides blue-collar work into those requiring non or basic skills and those requiring extensive training and higher skills.

According to the literature, the vulnerability of blue-collar jobs to technological change stems from, first, the competitive pressure to reduce the labour costs associated with labour-intensive industries through advances in robotics, automation, and AI technologies. Secondl the supposed superiority of technology to labour in performance efficiency, and reliability in noncognitive and routinised blue-collar work (e.g., Acemoglu & Autor, 2011; Arntz et al., 2016; Autor, 2015; Eurofound, 2018; Fernández-Macías, 2017; Frey & Osborne, 2013). These arguments, and predictions of imminent technological decimation of blue-collar jobs, go back many decades. Jeremy Rifkin, for example, argued in his seminal book, The End of Work, that ‘by the mid-21st Century, the blue-collar worker will have passed from history, a casualty of the Third Industrial Revolution’ (1995, p. 140). Such views are still common among more recent studies of Industry 4.0 and advanced manufacturing but are also found among studies of future of work in other traditional blue-collar industries including transport and logistics (T&L). According to the 2020 World Economic Forum (WEF) Report on the Future of Work, for example, the key future jobs in T&L include AI and machine learning specialists, digital analysts and scientists, software and applications developers and supply chain and logistics specialists rather than the'traditional’ occupations such as transport drivers, forklift operators and postal service clerks (WEF, 2020, p. 148). Despite these predictions many traditional blue-collar jobs, including those in T&L, are in strong demand across many countries with employers struggling to find workers willing to perform this study (see Cohen, 2021).https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ntwe.12259

To the average, dumb, soap opera watching person, lying a seet of bricks and concreting is seen as a unskiled job. But those of us that have tried to lift a wall or a fence, know how much work goes in lifting one that can stay up for years.

The National Trend in Blue-Collar Employment

In 1970, blue-collar jobs were 31.2 percent of total nonfarm employment. By 2016, their share had fallen to 13.6 percent of total employment. While blue-collar jobs have been declining as a share of total employment over this whole period, this was mostly due to the growth in total employment. The number of blue-collar jobs did not change much through most of this period. In 2000 there were 24.6 million blue-collar jobs, only slightly below the peak of 25.0 million in 1979. However the numbers plunged in the next decade due to the impact of the exploding trade deficit and the 2008-2009 recession. Blue-collar jobs fell to 17.8 million in 2010 and have since rebounded modestly to 19.6 million in the most recent data.

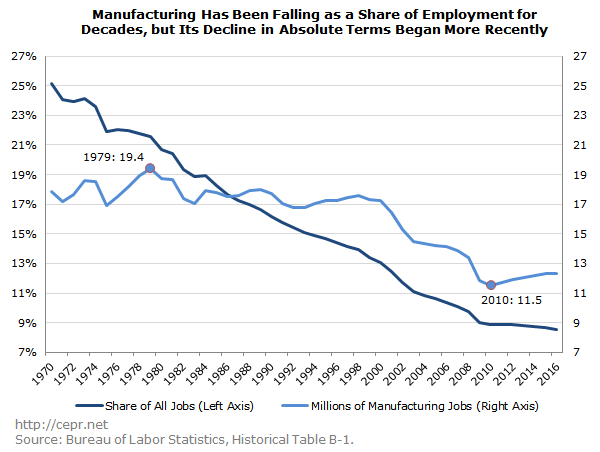

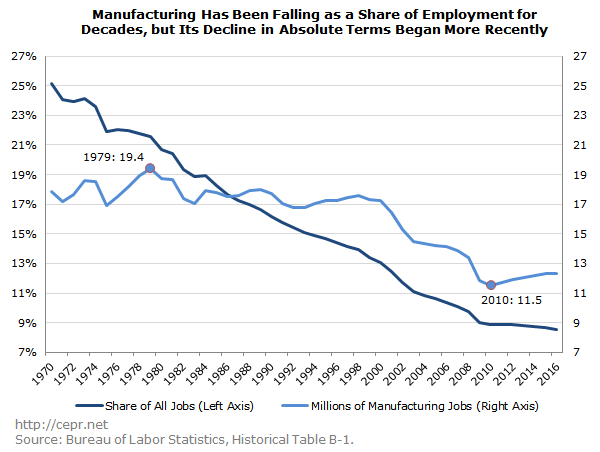

The National Trend in Manufacturing Jobs

Most of the secular change in blue-collar jobs has been in manufacturing. The figure below shows both the absolute number of manufacturing jobs (in millions) and manufacturing’s share of total nonfarm employment from 1970 to 2016. During the 70s, 80s, and 90s, the number of manufacturing jobs basically held steady, with about 17 to 19 million workers being employed in the sector each year. Manufacturing employment then declined every single year from 1998 to 2010. At present there are just 12.3 million manufacturing jobs in the United States.

Construction Fluctuates Cyclically, With No Secular Trend

Construction follows a somewhat different pattern. Construction employment is highly cyclical following patterns in the housing market, following the ups and downs in the business cycle, but it has little clear secular trend. In 2016, 4.7 percent of the workforce was employed in construction (6.7 million workers), with the figure heading upward over the course of the year. This is down from the 5.2 percent figure for 1970, but not out of line with the average for that decade.

The National Trend in Mining Jobs

Mining employment has largely followed the path of world energy prices as the bulk of employment in the sector is energy-related. Employment in the sector rose through the 1970s and peaked in 1982 at 1.2 percent of total employment. The collapse in world energy prices sent employment in the sector sharply lower in the next two decades, with employment in mining falling to just 0.4 percent of total employment in 1998. Higher energy prices and the fracking boom increased mining employment from 2003 until 2014. Since then, the plunge in energy prices sharply reduced employment, so it again stands at just 0.4 percent of total employment, with 626,000 total jobs in the sector.

- Lou Ferrigno and Arnold were proud brick layers

If the supply of workers interested in working in blue-collar jobs was growing as rapidly as demand, we would not have a problem. But in reality, the supply of workers for blue-collar jobs has been shrinking. People with a college degree are very unlikely to end up working in a blue-collar job, partly due to the stigma attached to manual labor. This is especially true in a tight labor market like the one the US is currently experiencing. The number of people in the labor force without a college degree could be used as a rough proxy of potential labor supply for blue-collar jobs. But as shown in the previous blog, this group of workers has been shrinking in recent years and will likely shrink even more rapidly in the coming decade.

Why is the supply of workers interested in blue-collar jobs shrinking?

The US working-age population has gotten more educated over time, with the share of the working-age population with no college degree declining significantly. Also, in recent years, an unusually large share of workers in blue-collar occupations have been retiring. This combination of many retirements and few new entrants is significantly reducing the supply of workers for blue-collar occupations. Since 2012, the number and share of people without a college degree has been shrinking. People with a college degree are much less likely to look for a blue-collar job.

https://cepr.net/publications/the-decline-of-blue-collar-jobs-in-graphs/

https://www.conference-board.org/re...ollar-Labor-Markets-Tighter-Than-White-Collar

Less educated Americans are much more likely not to be in the labor force due to disability.

The increasing share of more educated people in the US labor force is not just because the US population is becoming more educated. It is also because more non-college graduates are leaving the labor force due to disability. The increase in disability rates, partly because of the opioid epidemic, are much more concentrated in the population without a college degree and is therefore having a larger impact on the supply of workers to blue-collar and low-paid service occupations.

To be continued:

Last edited: