- Joined

- Apr 27, 2015

- Messages

- 828

- Reaction score

- 813

Continued from part 1 here.

In part one of Takedown Taxonomy, we looked at the basic, high-percentage takedown entries in MMA, breaking down their mechanics and optimal uses. Those entries will suffice for the majority of your wrestling needs and should integrate effectively into most fighting styles. But there’s always more than one way to skin a cat, and familiarity with tricky, less common takedown entries can be an ace up your sleeve.

Some of the advanced entries covered here are situational or dependent upon certain stance matchups. Others are ways to finesse an entry for fighters who lack the striking and comfort to create clean routes onto the hips. Whether you’re a clever striker looking to set up sneaky takedowns, or a wrestler who needs takedowns at all costs, there will be something in here that can integrate well into your process.

It may seem that the only options are to either bite the bullet and commit to single legs, or expend a lot of effort trying to set up awkward shifting double legs. But there is another way to exploit the near lead leg of an opponent standing opposite you. While penetration becomes messier, the leg is close enough to reach out and grab without penetrating onto the hips. It doesn’t carry us right into a takedown the way clean penetration does, but the shallow entry also takes less commitment, so we can keep harassing the lead leg until it’s time to shoot.

Unlike a double leg or a single leg, the shallow, one-handed grip on the leg does not put you in a position for an immediate finish. An extra step is needed to penetrate further and transition into a finish. But where the outside reach provides additional value is as a transitional tool. Since it’s not a full, committed entry, it can be seamlessly woven into feints, repeated over and over to frustrate an opponent and conceal the true entries, and even initiated simultaneously with a punch.

Merab Dvalishvili uses these entries liberally, and they’re one of the reasons he’s able to attempt a thousand takedowns every fight.

Dvalishvili will change levels and chuck a big overhand at his opponent while grabbing for their leg. If they focus on defending the takedown, they eat the punch, and he can bail easily with no wasted energy. But the overhand also attacks his opponent’s positioning, convincing them to straighten up and pull their weight over their rear foot. Then, without the ability to hip into him and counterbalance the takedown, Dvalishvili can run his feet forward, circling toward the leg for a high crotch, or stepping across for a double leg.

Reaching for the leg is simultaneously a takedown attempt, a setup for a big rear punch, and a weather vane to check the opponent’s response. It offers built-in, rote synergy between the entry and the punch, allowing you to repeat it over and over, forcing the opponent to guess which is coming and punishing them for choosing wrong.

Dvalishvili is a very rote fighter who tends to force attacks rather than creating subtle openings, but his constant use of the outside reach and overhand right means that he doesn’t have to worry about his opponent’s response in order to exploit it.

Every gesture toward the leg threatens both a big punch and a takedown, or even both at the same time. The opponent can never stay comfortable defending punches or takedowns, forced to expend precious mental resources on avoiding the space between them. But for the attacker, the attempt exposes and costs little, flowing in and out of transitions or making the opponent react to feints as he desires.

Since the open stance matchup provides a clear lane for the rear hand between the shoulders, there’s a lot of room to modify this entry depending on what our rear hand is doing. Overhands pair well with reaching into a double leg or high crotch, as the weight transfer of the overhand sinks the attacker’s weight down outside the defender’s lead hip.

But a straight rear hand opens up a classic MMA takedown, the knee pick:

Once the opponent has seen the rear straight a few times, we step forward and shift weight as if throwing it again, but target the chest instead of the head. The lead hand lifts the defender’s lead leg, and the threat of the rear hand moves their weight backwards, lightening the leg. The rear hand mashes into the chest and shoves the defender back, and we run forward until they topple over, unable to step their lead leg back to recover their base. With the right setup, it’s a quick and easy takedown that takes very little effort or energy.

The finishes covered so far can all be initiated from an upright posture, changing levels only after selling a punch and making contact with the leg. Entering shallow is ideal for transitional attacks, but we can make a quicker and more committed bid for the leg by throwing away the rear hand earlier and taking a deeper level change.

This was one of Glover Teixeira’s most consistent takedown entries:

As Teixeira throws his rear hand, he bends his knees and gets low, reaching outside the lead leg to secure the entry. His opponent’s vision is occupied by the punch and they remain upright while he ducks down onto their hips, stepping his rear leg through to attack an inside step double leg or high crotch.

If the rear hand is timed when the opponent steps in, it can be a powerful intercepting tool as well:

Chris Weidman times a rear straight as Tom Lawlor steps in with a lead hook. The natural fold in Weidman’s hips as he throws his rear hand takes him underneath the hook and puts him inches away from the leg. He quickly snags a grip outside the lead leg, his head already underneath Lawlor’s elbow, and Lawlor has to scramble to recovering his positioning, which gives Weidman time to finish clean.

Reaching outside the lead leg is mostly useful in open stance matchups, since the lead arm rests directly in front of the opponent’s lead leg, and the shoulder configuration leaves the chin open for the rear hand. Against an opponent in the same stance, the reach would have to occur with the rear hand, which sits much further from the opponent’s leg, and it loses synergy with a simultaneous punch.

Outside reach entries in same stance matchups are rare in MMA, but Frankie Edgar managed to build an effective system around them, so this next part will mostly be a case study on how Edgar made them work.

In part one of Takedown Taxonomy, we looked at the basic, high-percentage takedown entries in MMA, breaking down their mechanics and optimal uses. Those entries will suffice for the majority of your wrestling needs and should integrate effectively into most fighting styles. But there’s always more than one way to skin a cat, and familiarity with tricky, less common takedown entries can be an ace up your sleeve.

Some of the advanced entries covered here are situational or dependent upon certain stance matchups. Others are ways to finesse an entry for fighters who lack the striking and comfort to create clean routes onto the hips. Whether you’re a clever striker looking to set up sneaky takedowns, or a wrestler who needs takedowns at all costs, there will be something in here that can integrate well into your process.

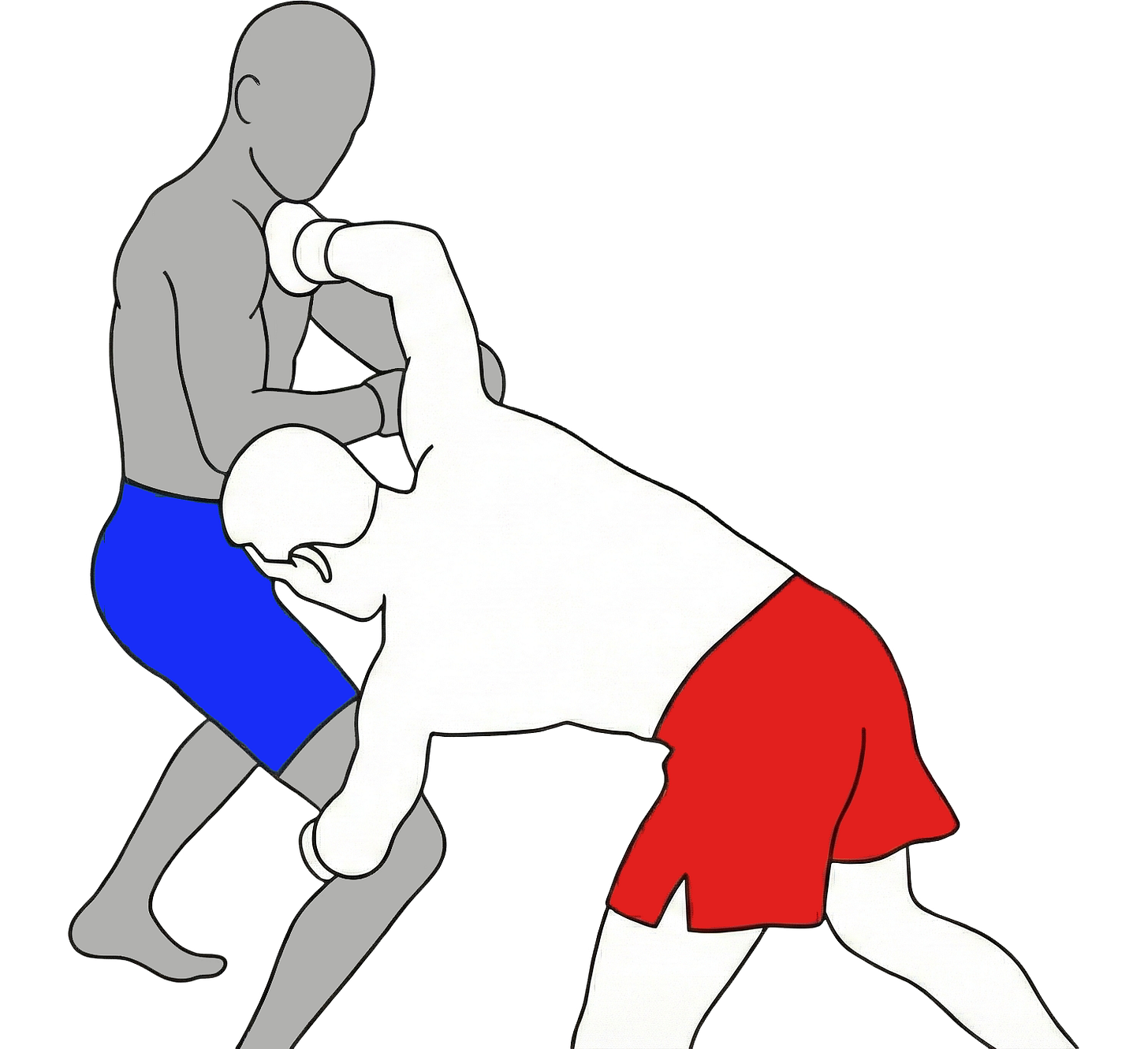

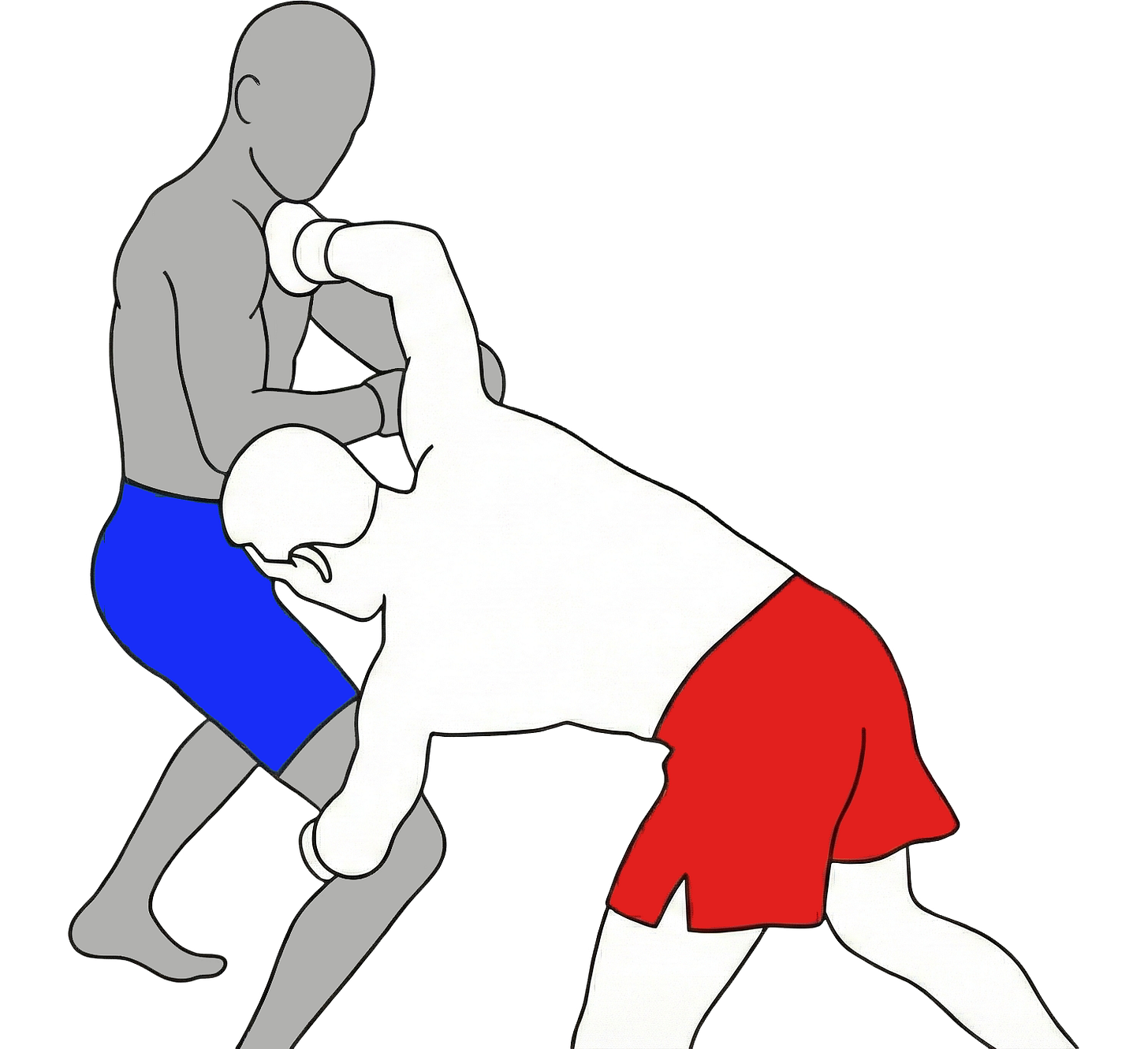

Outside Reach

In our previous discussion of outside step entries, we mentioned that shooting in on the hips of an opponent in the opposite stance is often awkward due to the distance and footwork involved. Although the clashing of the lead legs should, in theory, make it easier to reach the leg, it can be tricky to find clean entries in open stance for fighters who prefer the quick finish of a well-timed double leg over long chain wrestling sequences.It may seem that the only options are to either bite the bullet and commit to single legs, or expend a lot of effort trying to set up awkward shifting double legs. But there is another way to exploit the near lead leg of an opponent standing opposite you. While penetration becomes messier, the leg is close enough to reach out and grab without penetrating onto the hips. It doesn’t carry us right into a takedown the way clean penetration does, but the shallow entry also takes less commitment, so we can keep harassing the lead leg until it’s time to shoot.

Open Stance

What I’m referring to as an outside reach is an entry where the lead hand makes contact with the opponent’s lead leg while there’s still room between the fighters’ hips. It involves a shallow step forward, a slight level change - not enough to immediately tip off an incoming shot - and a reach outside the opponent’s lead leg.

Unlike a double leg or a single leg, the shallow, one-handed grip on the leg does not put you in a position for an immediate finish. An extra step is needed to penetrate further and transition into a finish. But where the outside reach provides additional value is as a transitional tool. Since it’s not a full, committed entry, it can be seamlessly woven into feints, repeated over and over to frustrate an opponent and conceal the true entries, and even initiated simultaneously with a punch.

Merab Dvalishvili uses these entries liberally, and they’re one of the reasons he’s able to attempt a thousand takedowns every fight.

Dvalishvili will change levels and chuck a big overhand at his opponent while grabbing for their leg. If they focus on defending the takedown, they eat the punch, and he can bail easily with no wasted energy. But the overhand also attacks his opponent’s positioning, convincing them to straighten up and pull their weight over their rear foot. Then, without the ability to hip into him and counterbalance the takedown, Dvalishvili can run his feet forward, circling toward the leg for a high crotch, or stepping across for a double leg.

Reaching for the leg is simultaneously a takedown attempt, a setup for a big rear punch, and a weather vane to check the opponent’s response. It offers built-in, rote synergy between the entry and the punch, allowing you to repeat it over and over, forcing the opponent to guess which is coming and punishing them for choosing wrong.

Dvalishvili is a very rote fighter who tends to force attacks rather than creating subtle openings, but his constant use of the outside reach and overhand right means that he doesn’t have to worry about his opponent’s response in order to exploit it.

Every gesture toward the leg threatens both a big punch and a takedown, or even both at the same time. The opponent can never stay comfortable defending punches or takedowns, forced to expend precious mental resources on avoiding the space between them. But for the attacker, the attempt exposes and costs little, flowing in and out of transitions or making the opponent react to feints as he desires.

Since the open stance matchup provides a clear lane for the rear hand between the shoulders, there’s a lot of room to modify this entry depending on what our rear hand is doing. Overhands pair well with reaching into a double leg or high crotch, as the weight transfer of the overhand sinks the attacker’s weight down outside the defender’s lead hip.

But a straight rear hand opens up a classic MMA takedown, the knee pick:

Once the opponent has seen the rear straight a few times, we step forward and shift weight as if throwing it again, but target the chest instead of the head. The lead hand lifts the defender’s lead leg, and the threat of the rear hand moves their weight backwards, lightening the leg. The rear hand mashes into the chest and shoves the defender back, and we run forward until they topple over, unable to step their lead leg back to recover their base. With the right setup, it’s a quick and easy takedown that takes very little effort or energy.

The finishes covered so far can all be initiated from an upright posture, changing levels only after selling a punch and making contact with the leg. Entering shallow is ideal for transitional attacks, but we can make a quicker and more committed bid for the leg by throwing away the rear hand earlier and taking a deeper level change.

This was one of Glover Teixeira’s most consistent takedown entries:

As Teixeira throws his rear hand, he bends his knees and gets low, reaching outside the lead leg to secure the entry. His opponent’s vision is occupied by the punch and they remain upright while he ducks down onto their hips, stepping his rear leg through to attack an inside step double leg or high crotch.

If the rear hand is timed when the opponent steps in, it can be a powerful intercepting tool as well:

Chris Weidman times a rear straight as Tom Lawlor steps in with a lead hook. The natural fold in Weidman’s hips as he throws his rear hand takes him underneath the hook and puts him inches away from the leg. He quickly snags a grip outside the lead leg, his head already underneath Lawlor’s elbow, and Lawlor has to scramble to recovering his positioning, which gives Weidman time to finish clean.

Reaching outside the lead leg is mostly useful in open stance matchups, since the lead arm rests directly in front of the opponent’s lead leg, and the shoulder configuration leaves the chin open for the rear hand. Against an opponent in the same stance, the reach would have to occur with the rear hand, which sits much further from the opponent’s leg, and it loses synergy with a simultaneous punch.

Outside reach entries in same stance matchups are rare in MMA, but Frankie Edgar managed to build an effective system around them, so this next part will mostly be a case study on how Edgar made them work.