- Joined

- Jan 17, 2010

- Messages

- 8,613

- Reaction score

- 10,811

A movie by John McTiernan

Starring Sylvester Stallone, Kevin Costner, 50 Cent, Sandra Bullock and Fred Ward

With Shia LaBeouf as @nhbbear

Marnette Gordon was doing laundry at home in Minneapolis one summer morning last year when a call came from her 36-year-old son.

She figured her son, Telly Blair, was checking in to see if she wanted a soda from a gas station down the street, where he often went for fuel and snacks.

“Mom, I’ve been shot,” he said. “Call the police!”

Marnette, her other son Tamarcus and his 12-year-old daughter rushed to the gas station from their home in the city’s north side, a part of town long beset by violent crime.

Blair’s family came upon his blue 1986 Chevy Caprice at pump No. 5 — beating police and paramedics by a few minutes, they said — only to find him slumped in his car, bleeding from multiple bullet wounds in his chest. A 17-year-old male in an orange hoodie had fired nine rounds from a handgun into Blair’s car before running off.

While an off-duty nurse in scrubs who’d been at the gas station tried to stop his bleeding, Marnette — a heart-transplant recipient — couldn’t bear to watch and stood at a distance. Telly was her caretaker.

“It was just horrible to see him sitting there, waiting on the ambulance,” she told CNN.

The 12-year-old called 911 while watching her uncle struggle to breathe.

“Oh my God, please,” the girl, who was crying, said to a dispatcher, according to 911 transcripts of the August 9, 2021 shooting obtained by CNN. “Hurry up, hurry up, hurry, hurry, he’s dead, hurry up!”

Telly Blair was among 93 people who were murdered in Minneapolis last year, city crime data shows. That’s just a few shy of the total killings in 1995, when the city earned the nickname “Murderapolis.” (Neighboring St. Paul witnessed 38 murders last year — a historic high.)

After the police murder of George Floyd in May of 2020, Minneapolis became a worldwide symbol of the police brutality long endured disproportionately by Black people. In a kind of Newtonian response, the city became the epicenter of the culturally seismic “Defund the Police” movement. But that progressive local effort fizzled with a decisive referendum last November.

Now, with its police department under investigation by the Department of Justice, the city of 425,000 is trying to find a way forward amid a period of heightened crime that began shortly after Floyd’s death.

That year, the number of murders soared to nearly 80 — dwarfing the 2019 body count of 46. It has cooled somewhat this year, though the amount of killing — and violent crime in general — remains elevated far above 2019 levels and homicides are on pace to surpass the 2020 figure. The reasons why are far from clear.

KG Wilson, a longtime resident of the Twin Cities, said police withdrew from violent neighborhoods in the aftermath of Floyd’s killing — a common sentiment among locals.

“The criminals were celebrating. They were getting rich,” he said. “They were selling drugs openly.”

Wilson told CNN the violence devastated his own family: His 6-year-old granddaughter was killed in May of 2021 after getting caught in the crossfire of a gunfight in north Minneapolis. The culprit remains at large.

Another factor was the pandemic, which some observers see as the biggest impetus for the crime surge.

“It unsettled settled trajectories,” said Mark Osler, a former federal prosecutor who is now a professor at St. Thomas School of Law in Minneapolis. “Kids who were going to school, who would have graduated but drifted off because there is no school — we’re seeing a lot of the violent crime is by juveniles.”

Citing sinking morale in the wake of the unrest after Floyd’s killing, leaders at the Minneapolis Police Department say the officer head count has shrunk from 900 in early 2020 to about 560 in August — a loss of more than a third of the force.

Against this backdrop, the political pendulum on public-safety matters in this reliably liberal city — the “Mini Apple” hasn’t had a Republican mayor since 1973, and that was for just a single day — seems to have swung away from a progressive mindset towards the middle.

And on matters of public safety, the middle is where many of the city’s Black residents already were.

Last year, progressives touted a ballot measure that was said to be a referendum on the “defund” concept. Question 2, as it was known locally, would have replaced the Minneapolis Police Department with a new “public health-oriented” Department of Public Safety and removed a minimum staffing requirement from the city charter.

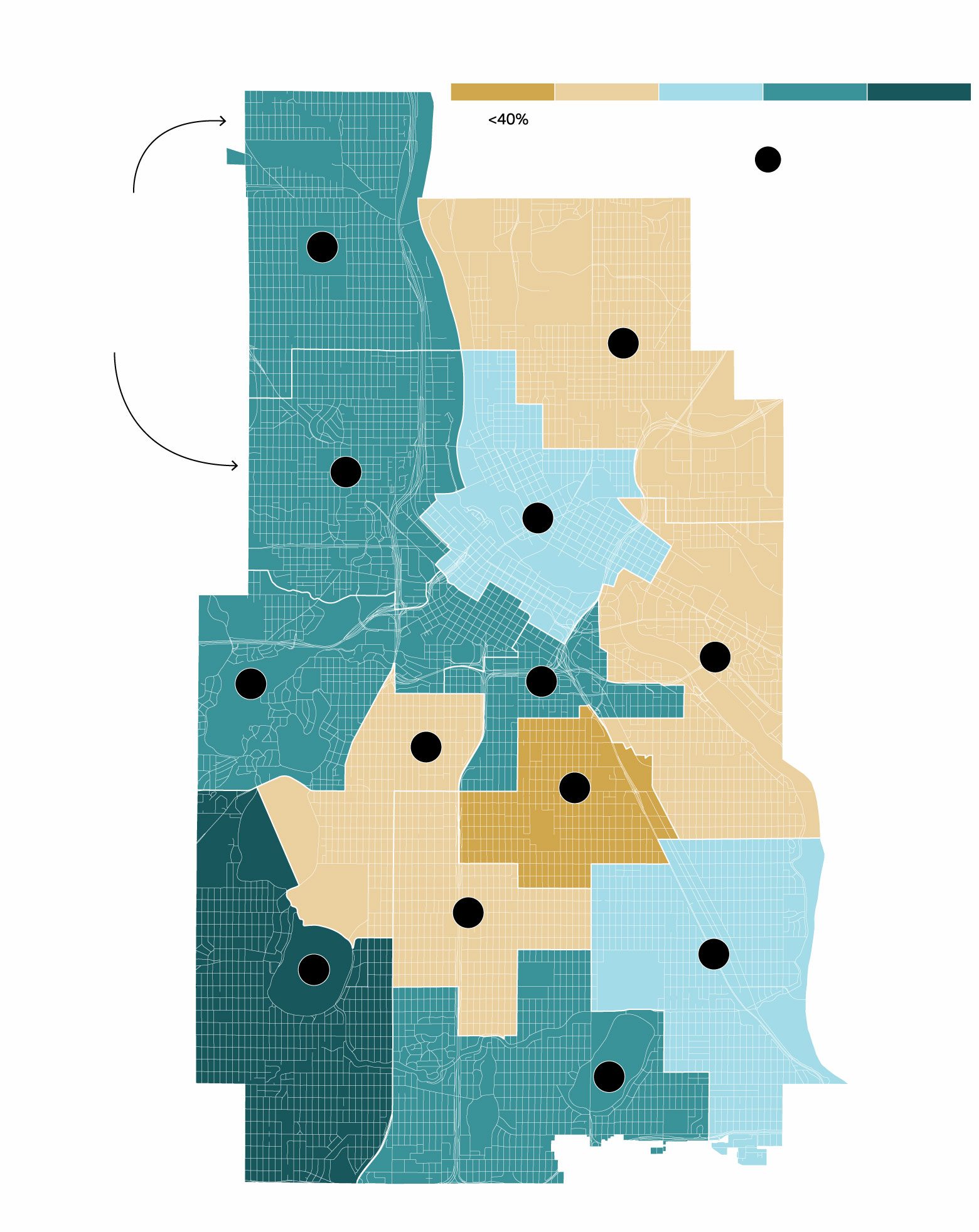

It failed in November, with 56% of voters rejecting it. That figure was 61% in north Minneapolis, a pair of neighboring city wards where Blacks make up a strong plurality of the roughly 66,000 residents. All but one of the 17 precincts in the north voted against the measure.

KG Wilson created a memorial for his granddaughter Aniya Allen in his SUV. The car seat cover of her face rests on the seat where she would ride with him.

Andrea Ellen Reed for CNN

“We did not believe that the police should be defunded, but we do believe in police reforms,” said Bishop Richard Howell of Shiloh Temple, a north-side church founded more than 90 years ago.

Rae McKay-Anderson — Telly Blair’s sister — said “you can’t possibly defund the police in a way that’s going to benefit the Black community.”

Dealing the final blow to the local “defund” movement last year was a city council vote to essentially refund a cut they’d made the prior year. Mayor Jacob Frey is proposing another budget bump for the next two fiscal years.

The question of the moment is, if the police budget has been restored, and if all the anti-cop shouting by politicians and activists that left officers demoralized has weakened to a whimper, why are citizens — especially in the rough parts of north Minneapolis — still feeling neglected by police and fearful for their safety?

Paul Johnson, 56, said young men openly sell drugs during the day in public places, such as a gas station on Broadway Avenue that has been dubbed the “murder station” due to all of the fatal shootings there. (It is near the one where Blair was killed.)

“You pull up to get gas – they try to sell you drugs,” he said. “And not just three or four, but it’s a bulk of people.”

The perception among many residents is that the police ignore the area.

“They just let it go on,” said Johnson’s friend, Brian Bogan, 42, who said he moved from north Minneapolis to relatively safer St. Paul due to his kids growing up in an area where they don’t know if “it’s fireworks or gunshots.”

While Minneapolis is far from the nation’s most dangerous city, its rate of increase in homicides — the count in 2021 was about double that of 2019 — is among the highest in the nation, said Richard Rosenfeld, a criminologist at the University of Missouri- St. Louis and co-author of an annual study on crime trends.

On per-capita murders, it has ranked fairly high — 19th out of 70 jurisdictions in the US — during the first half of this year, according to the Major Cities Chiefs Association. The city ranked even higher on other per-capita crime measures, such as robbery (4th), rape (8th) and aggravated assault (13th).

Juliee Oden, 56, can’t even count the times she has called 911 to report gunfire outside her north-side home. One night last summer, a volley of shots jolted her out of bed while she was watching TV — it was coming from her front lawn.

“I hit the floor,” she said. “My phone went flying. I had to crawl on my stomach to get to the phone” to dial 911.

It got to the point where it was hard to sleep at night and Oden, who works at a construction company, had colleagues install a bulletproof panel behind the headboard of her bed.

“Now I go in my room with complete confidence,” she said. “If somebody is to shoot directly at my house, I know: As long as I’m behind my headboard, I’m 100% safe.”

A memorial for Aniya Allen lay on the ground of the corner store near where she was shot in north Minneapolis.

Andrea Ellen Reed for CNN

Oden was among eight residents in north Minneapolis who filed a lawsuit in the summer of 2020 calling on the city to replenish the police department by filling vacant positions. The suit singled out city council members who supported the “radical ‘dismantle the police’” idea and accused them and Mayor Frey of creating a “hostile” environment for the police. It was largely upheld by a state Supreme Court decision this summer — meaning the city needs to staff up to at least 731 police officers.

Doug Seaton, an attorney representing the eight residents, said the successful suit was filed in direct response to how progressive city council members had embraced the “defund” idea. It demoralized the police department and ultimately led to a mass exodus of officers, he said.

“That is, we think, the major reason that crime has spiked throughout the city and hasn’t gone away yet,” Seaton said.

Meanwhile, as the MPD headcount has shrunk, wait times have grown for people who call 911 to report serious “priority 1” incidents, which can include shots fired, robberies, assaults and mental health crises.

Average 911 response times jumped the very month of Floyd’s death — May of 2020 — from around 10 or 11 minutes early that year to 14 minutes, according to public records obtained by CNN. They kept rising in 2021 to 16 minutes; response times in the north side’s fourth precinct last year actually surpassed 17 minutes, where they remain.

To ber continued!

Starring Sylvester Stallone, Kevin Costner, 50 Cent, Sandra Bullock and Fred Ward

With Shia LaBeouf as @nhbbear

Marnette Gordon was doing laundry at home in Minneapolis one summer morning last year when a call came from her 36-year-old son.

She figured her son, Telly Blair, was checking in to see if she wanted a soda from a gas station down the street, where he often went for fuel and snacks.

“Mom, I’ve been shot,” he said. “Call the police!”

Marnette, her other son Tamarcus and his 12-year-old daughter rushed to the gas station from their home in the city’s north side, a part of town long beset by violent crime.

Blair’s family came upon his blue 1986 Chevy Caprice at pump No. 5 — beating police and paramedics by a few minutes, they said — only to find him slumped in his car, bleeding from multiple bullet wounds in his chest. A 17-year-old male in an orange hoodie had fired nine rounds from a handgun into Blair’s car before running off.

While an off-duty nurse in scrubs who’d been at the gas station tried to stop his bleeding, Marnette — a heart-transplant recipient — couldn’t bear to watch and stood at a distance. Telly was her caretaker.

“It was just horrible to see him sitting there, waiting on the ambulance,” she told CNN.

The 12-year-old called 911 while watching her uncle struggle to breathe.

“Oh my God, please,” the girl, who was crying, said to a dispatcher, according to 911 transcripts of the August 9, 2021 shooting obtained by CNN. “Hurry up, hurry up, hurry, hurry, he’s dead, hurry up!”

Telly Blair was among 93 people who were murdered in Minneapolis last year, city crime data shows. That’s just a few shy of the total killings in 1995, when the city earned the nickname “Murderapolis.” (Neighboring St. Paul witnessed 38 murders last year — a historic high.)

After the police murder of George Floyd in May of 2020, Minneapolis became a worldwide symbol of the police brutality long endured disproportionately by Black people. In a kind of Newtonian response, the city became the epicenter of the culturally seismic “Defund the Police” movement. But that progressive local effort fizzled with a decisive referendum last November.

Now, with its police department under investigation by the Department of Justice, the city of 425,000 is trying to find a way forward amid a period of heightened crime that began shortly after Floyd’s death.

That year, the number of murders soared to nearly 80 — dwarfing the 2019 body count of 46. It has cooled somewhat this year, though the amount of killing — and violent crime in general — remains elevated far above 2019 levels and homicides are on pace to surpass the 2020 figure. The reasons why are far from clear.

KG Wilson, a longtime resident of the Twin Cities, said police withdrew from violent neighborhoods in the aftermath of Floyd’s killing — a common sentiment among locals.

“The criminals were celebrating. They were getting rich,” he said. “They were selling drugs openly.”

Wilson told CNN the violence devastated his own family: His 6-year-old granddaughter was killed in May of 2021 after getting caught in the crossfire of a gunfight in north Minneapolis. The culprit remains at large.

Another factor was the pandemic, which some observers see as the biggest impetus for the crime surge.

“It unsettled settled trajectories,” said Mark Osler, a former federal prosecutor who is now a professor at St. Thomas School of Law in Minneapolis. “Kids who were going to school, who would have graduated but drifted off because there is no school — we’re seeing a lot of the violent crime is by juveniles.”

Citing sinking morale in the wake of the unrest after Floyd’s killing, leaders at the Minneapolis Police Department say the officer head count has shrunk from 900 in early 2020 to about 560 in August — a loss of more than a third of the force.

Against this backdrop, the political pendulum on public-safety matters in this reliably liberal city — the “Mini Apple” hasn’t had a Republican mayor since 1973, and that was for just a single day — seems to have swung away from a progressive mindset towards the middle.

And on matters of public safety, the middle is where many of the city’s Black residents already were.

Last year, progressives touted a ballot measure that was said to be a referendum on the “defund” concept. Question 2, as it was known locally, would have replaced the Minneapolis Police Department with a new “public health-oriented” Department of Public Safety and removed a minimum staffing requirement from the city charter.

It failed in November, with 56% of voters rejecting it. That figure was 61% in north Minneapolis, a pair of neighboring city wards where Blacks make up a strong plurality of the roughly 66,000 residents. All but one of the 17 precincts in the north voted against the measure.

KG Wilson created a memorial for his granddaughter Aniya Allen in his SUV. The car seat cover of her face rests on the seat where she would ride with him.

Andrea Ellen Reed for CNN

“We did not believe that the police should be defunded, but we do believe in police reforms,” said Bishop Richard Howell of Shiloh Temple, a north-side church founded more than 90 years ago.

Rae McKay-Anderson — Telly Blair’s sister — said “you can’t possibly defund the police in a way that’s going to benefit the Black community.”

Dealing the final blow to the local “defund” movement last year was a city council vote to essentially refund a cut they’d made the prior year. Mayor Jacob Frey is proposing another budget bump for the next two fiscal years.

The question of the moment is, if the police budget has been restored, and if all the anti-cop shouting by politicians and activists that left officers demoralized has weakened to a whimper, why are citizens — especially in the rough parts of north Minneapolis — still feeling neglected by police and fearful for their safety?

A feeling of lawlessness, a sense of neglect

Residents of the north side describe a landscape that can feel lawless. Indeed, about 60% of police calls for shots fired this year have come from the area, even though it makes up just 15% of the population, according to city data.Paul Johnson, 56, said young men openly sell drugs during the day in public places, such as a gas station on Broadway Avenue that has been dubbed the “murder station” due to all of the fatal shootings there. (It is near the one where Blair was killed.)

“You pull up to get gas – they try to sell you drugs,” he said. “And not just three or four, but it’s a bulk of people.”

The perception among many residents is that the police ignore the area.

“They just let it go on,” said Johnson’s friend, Brian Bogan, 42, who said he moved from north Minneapolis to relatively safer St. Paul due to his kids growing up in an area where they don’t know if “it’s fireworks or gunshots.”

While Minneapolis is far from the nation’s most dangerous city, its rate of increase in homicides — the count in 2021 was about double that of 2019 — is among the highest in the nation, said Richard Rosenfeld, a criminologist at the University of Missouri- St. Louis and co-author of an annual study on crime trends.

On per-capita murders, it has ranked fairly high — 19th out of 70 jurisdictions in the US — during the first half of this year, according to the Major Cities Chiefs Association. The city ranked even higher on other per-capita crime measures, such as robbery (4th), rape (8th) and aggravated assault (13th).

Juliee Oden, 56, can’t even count the times she has called 911 to report gunfire outside her north-side home. One night last summer, a volley of shots jolted her out of bed while she was watching TV — it was coming from her front lawn.

“I hit the floor,” she said. “My phone went flying. I had to crawl on my stomach to get to the phone” to dial 911.

It got to the point where it was hard to sleep at night and Oden, who works at a construction company, had colleagues install a bulletproof panel behind the headboard of her bed.

“Now I go in my room with complete confidence,” she said. “If somebody is to shoot directly at my house, I know: As long as I’m behind my headboard, I’m 100% safe.”

A memorial for Aniya Allen lay on the ground of the corner store near where she was shot in north Minneapolis.

Andrea Ellen Reed for CNN

Oden was among eight residents in north Minneapolis who filed a lawsuit in the summer of 2020 calling on the city to replenish the police department by filling vacant positions. The suit singled out city council members who supported the “radical ‘dismantle the police’” idea and accused them and Mayor Frey of creating a “hostile” environment for the police. It was largely upheld by a state Supreme Court decision this summer — meaning the city needs to staff up to at least 731 police officers.

Doug Seaton, an attorney representing the eight residents, said the successful suit was filed in direct response to how progressive city council members had embraced the “defund” idea. It demoralized the police department and ultimately led to a mass exodus of officers, he said.

“That is, we think, the major reason that crime has spiked throughout the city and hasn’t gone away yet,” Seaton said.

Meanwhile, as the MPD headcount has shrunk, wait times have grown for people who call 911 to report serious “priority 1” incidents, which can include shots fired, robberies, assaults and mental health crises.

Average 911 response times jumped the very month of Floyd’s death — May of 2020 — from around 10 or 11 minutes early that year to 14 minutes, according to public records obtained by CNN. They kept rising in 2021 to 16 minutes; response times in the north side’s fourth precinct last year actually surpassed 17 minutes, where they remain.

To ber continued!