- Joined

- Mar 27, 2004

- Messages

- 10,223

- Reaction score

- 5,193

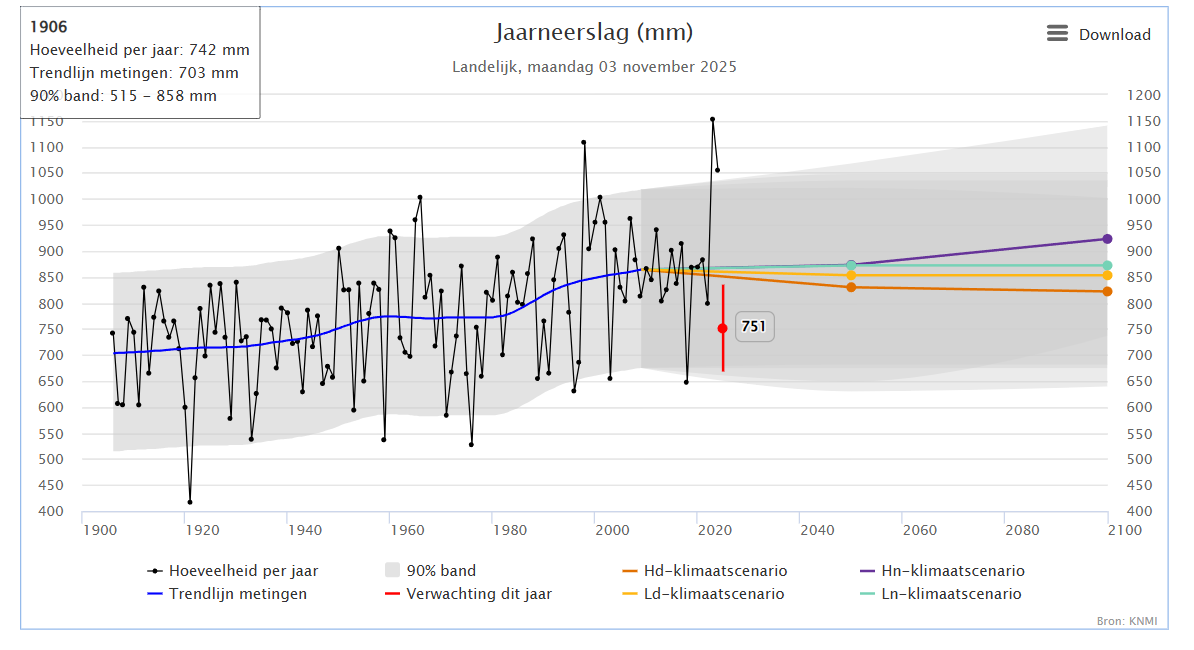

There's no trend that shows we're getting less rain. Highest rainfall in the chart is in 2023 (half of the paths in my hometown forest were blocked by standing water), now we have a below average year. Shit has always been fluctuating wildly. I see zero reason for concern just because we've had one dry year.

It may not be quite that simple. Increased heat means increased evaporation which can lead to drier conditions even if the total rainfall has increased or is stable. Also patterns are changing, and there could be more extremes. Winters may be wetter and summers could see periods of longer drought as well as shorter more intense downpours. I know that there are a lot of "Could be" or "May be" in my reply but studying weather/climate patterns is complex with multiple factors.

Last edited: