- Joined

- Jan 17, 2010

- Messages

- 9,810

- Reaction score

- 12,450

Trump has said he wants to use active duty U.S. troops to quell protests and round up immigrants. Will the military comply?

A movie by Albert Pyun(RIP)

Starring Gary Daniels, Evan Lurie, Angie Everhart

Michael Hirsh is the former foreign editor and chief diplomatic correspondent for Newsweek, and the former national editor for POLITICO Magazine.

The last time an American president deployed the U.S. military domestically under the Insurrection Act — during the deadly Los Angeles riots in 1992 — Douglas Ollivant was there. Ollivant, then a young Army first lieutenant, says things went fairly smoothly because it was somebody else — the cops — doing the head-cracking to restore order, not his 7th Infantry Division. He and his troops didn’t have to detain or shoot at anyone.

“There was real sensitivity about keeping federal troops away from the front lines,” said Ollivant, who was ordered in by President George H.W. Bush as rioters in central-south LA set fire to buildings, assaulted police and bystanders, pelted cars with rocks and smashed store windows in the aftermath of the videotaped police beating of Rodney King, a Black motorist. “They tried to keep us in support roles, backing up the police.”

By the end of six days of rioting, 63 people were dead and 2,383 injured — though reportedly none at the hands of the military.

But some in the U.S. military fear next time could be different. According to nearly a dozen retired officers and current military lawyers, as well as scholars who teach at West Point and Annapolis, an intense if quiet debate is underway inside the U.S. military community about what orders it would be obliged to obey if President-elect Donald Trump decides to follow through on his previous warnings that he might deploy troops against what he deems domestic threats, including political enemies, dissenters and immigrants.

On Nov. 18, two weeks after the election, Trump confirmed he plans to declare a national emergency and use the military for the mass deportations of illegal immigrants.

One fear is that domestic deployment of active-duty troops could lead to bloodshed given that the regular military is mainly trained to shoot at and kill foreign enemies. The only way to prevent that is establishing clear “rules of engagement” for domestic deployments that outline how much force troops can use — especially considering constitutional restraints protecting U.S. citizens and residents — against what kinds of people in what kinds of situations. And establishing those new rules would require a lot more training, in the view of many in the military community.

“Everything I hear is that our training is in the shitter,” says retired Army Lt. Gen. Marvin Covault, who commanded the 7th Infantry Division in 1992 in what was called “Joint Task Force LA.” “I’m not sure we have the kind of discipline now, and at every leader level, that we had 32 years ago. That concerns me about the people you’re going to put on the ground.”

In an interview, Covault said he was careful to avoid lethal force in Los Angeles by emphasizing to his soldiers they were now “deployed in the civilian world.” He ordered gun chambers to remain empty except in self-defense, banned all automatic weapons and required bayonets to remain on soldiers’ belts.

But Covault added that he set those rules at his own discretion. Even then Covault said he faced some recalcitrance, especially from U.S. Marine battalions under his command that sought to keep M16 machine guns on their armored personnel carriers. In one reported case a Marine unit, asked by L.A. police for “cover,” misunderstood the police term for “standing by” and fired some 200 rounds at a house occupied by a family. Fortunately, no one was injured.

“If we get fast and loose with rules of engagement or if we get into operations without a stated mission and intent, we’re going to be headline news, and it’s not going to be good,” Covault said in the interview.

Trump has repeatedly said he might use the military to suppress a domestic protest, or to raid a sanctuary city to purge it of undocumented immigrants, or possibly defend the Southern border. Some in the military community say they are especially disturbed by the prospect that troops might be used to serve Trump’s political ends. In 1992, Covault said, he had no direct orders from Bush other than to deploy to restore peace. On his own volition, he said, he announced upon landing in LA at a news conference: “This is not martial law. The reason we’re here is to create a safe and secure environment so you can go back to normal.” Covault said he believes the statement had a calming effect.

But 28 years later, when the police killing of another Black American, George Floyd, sparked sporadically violent protests nationwide, then-President Trump openly considered using firepower on the demonstrators, according to his former defense secretary, Mark Esper. Trump asked, “Can’t you just shoot them? Just shoot them in the legs or something?” Esper wrote in his 2022 memoir, A Sacred Trust. At another point Trump urged his Joint Chiefs chair, Gen. Mark Milley, to “beat the fuck out” out of the protesters and “crack skulls,” and he tweeted that “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.” Esper wrote that he had “to walk Trump back” from such ideas and the president didn’t pursue them.

Some involved in the current debate say they are worried Trump would not be as restrained this time. He is filling his Pentagon and national security team with fierce loyalists. The concern is not just in how much force might be used, but also whether troops would be regularly deployed to advance the new administration’s political interests.

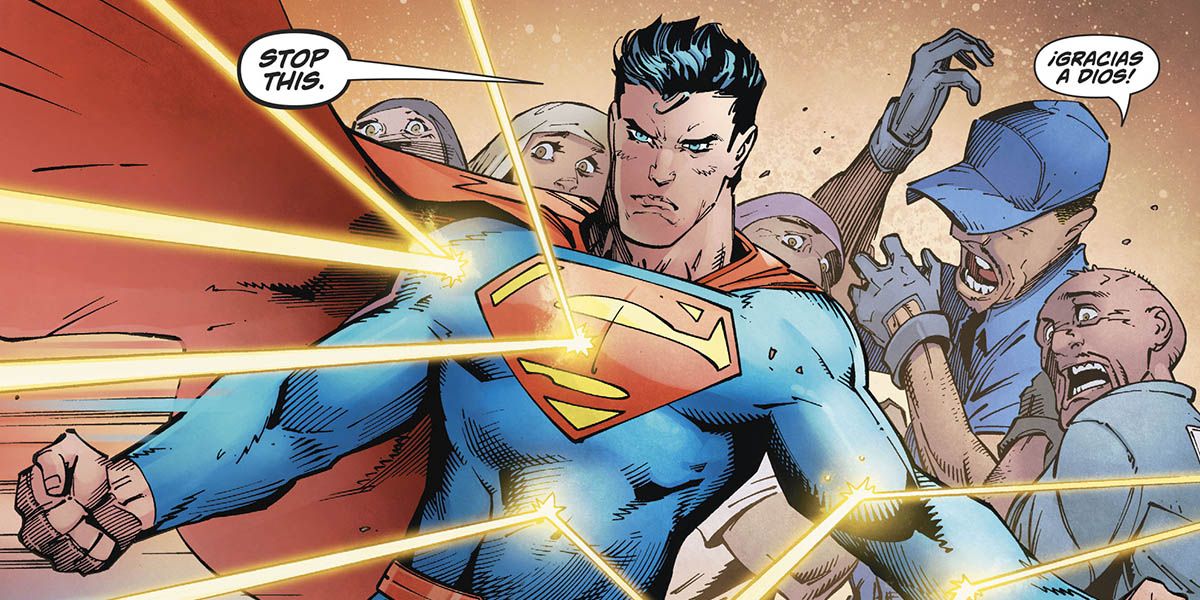

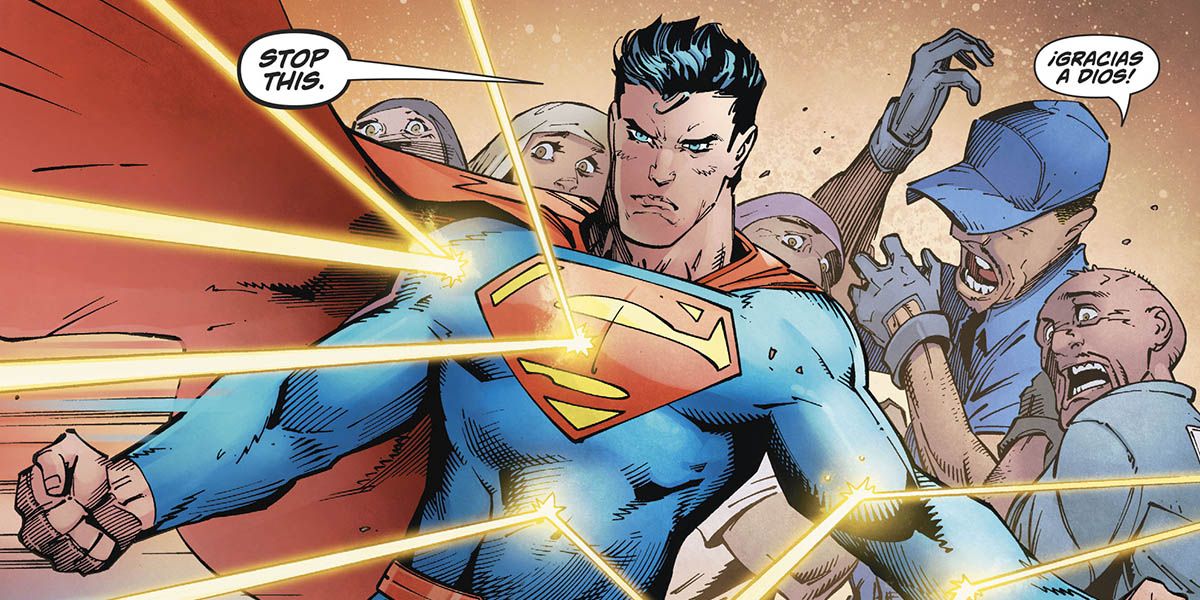

https://www.cbr.com/of-course-superman-saved-immigrant-workers-its-what-he-does/

This topic is extremely sensitive inside the active-duty military, and a Pentagon spokesperson declined to comment. But several of the retired military officials I interviewed said that they were gingerly talking about it with their friends and colleagues still in active service.

And Mark Zaid, a Washington lawyer who has long represented military and intelligence officers who run afoul of their chain of command, told me: “A lot of people are reaching out to me proactively to express concern about what they foresee coming, including Defense Department civilians and active-duty military.” Among them, Zaid said, are people “who are either planning on leaving the government or will be waiting to see if there is a line that is crossed by the incoming administration.”

After the D.C. National Guard was ordered to clear demonstrators from Lafayette Square across from the White House in 2020 using tear gas, rubber bullets and flash-bang grenades, a group of lawyers founded “The Orders Project” aimed at connecting up lawyers and troops looking for legal advice.

One of the founders, Eugene Fidell of Yale Law School, said that the group disbanded after the first Trump administration but is now being resurrected.

“With the return of President Trump, we’re ready to help people in need,” Fidell said.

The Lafayette Square incident remains a topic of some debate inside the military community. One DC guardsman, Major Adam DeMarco, an Iraq war veteran, later said in written testimony to Congress that he was “deeply disturbed” by the “excessive use of force.” “Having served in a combat zone, and understanding how to assess threat environments, at no time did I feel threatened by the protesters or assess them to be violent,” he wrote. “I knew something was wrong, but I didn’t know what. Anthony Pfaff, a retired colonel who is now a military ethics scholar at the U.S. Army War College, said this confusion reveals a serious training deficiency: Domestic crowd control and policing “is not something for which we have any doctrine or other standard operating procedures. Without those, thresholds for force could be determined by individual commanders, leading to even more confusion.”

A movie by Albert Pyun(RIP)

Starring Gary Daniels, Evan Lurie, Angie Everhart

Michael Hirsh is the former foreign editor and chief diplomatic correspondent for Newsweek, and the former national editor for POLITICO Magazine.

The last time an American president deployed the U.S. military domestically under the Insurrection Act — during the deadly Los Angeles riots in 1992 — Douglas Ollivant was there. Ollivant, then a young Army first lieutenant, says things went fairly smoothly because it was somebody else — the cops — doing the head-cracking to restore order, not his 7th Infantry Division. He and his troops didn’t have to detain or shoot at anyone.

“There was real sensitivity about keeping federal troops away from the front lines,” said Ollivant, who was ordered in by President George H.W. Bush as rioters in central-south LA set fire to buildings, assaulted police and bystanders, pelted cars with rocks and smashed store windows in the aftermath of the videotaped police beating of Rodney King, a Black motorist. “They tried to keep us in support roles, backing up the police.”

By the end of six days of rioting, 63 people were dead and 2,383 injured — though reportedly none at the hands of the military.

But some in the U.S. military fear next time could be different. According to nearly a dozen retired officers and current military lawyers, as well as scholars who teach at West Point and Annapolis, an intense if quiet debate is underway inside the U.S. military community about what orders it would be obliged to obey if President-elect Donald Trump decides to follow through on his previous warnings that he might deploy troops against what he deems domestic threats, including political enemies, dissenters and immigrants.

On Nov. 18, two weeks after the election, Trump confirmed he plans to declare a national emergency and use the military for the mass deportations of illegal immigrants.

One fear is that domestic deployment of active-duty troops could lead to bloodshed given that the regular military is mainly trained to shoot at and kill foreign enemies. The only way to prevent that is establishing clear “rules of engagement” for domestic deployments that outline how much force troops can use — especially considering constitutional restraints protecting U.S. citizens and residents — against what kinds of people in what kinds of situations. And establishing those new rules would require a lot more training, in the view of many in the military community.

“Everything I hear is that our training is in the shitter,” says retired Army Lt. Gen. Marvin Covault, who commanded the 7th Infantry Division in 1992 in what was called “Joint Task Force LA.” “I’m not sure we have the kind of discipline now, and at every leader level, that we had 32 years ago. That concerns me about the people you’re going to put on the ground.”

In an interview, Covault said he was careful to avoid lethal force in Los Angeles by emphasizing to his soldiers they were now “deployed in the civilian world.” He ordered gun chambers to remain empty except in self-defense, banned all automatic weapons and required bayonets to remain on soldiers’ belts.

But Covault added that he set those rules at his own discretion. Even then Covault said he faced some recalcitrance, especially from U.S. Marine battalions under his command that sought to keep M16 machine guns on their armored personnel carriers. In one reported case a Marine unit, asked by L.A. police for “cover,” misunderstood the police term for “standing by” and fired some 200 rounds at a house occupied by a family. Fortunately, no one was injured.

“If we get fast and loose with rules of engagement or if we get into operations without a stated mission and intent, we’re going to be headline news, and it’s not going to be good,” Covault said in the interview.

Trump has repeatedly said he might use the military to suppress a domestic protest, or to raid a sanctuary city to purge it of undocumented immigrants, or possibly defend the Southern border. Some in the military community say they are especially disturbed by the prospect that troops might be used to serve Trump’s political ends. In 1992, Covault said, he had no direct orders from Bush other than to deploy to restore peace. On his own volition, he said, he announced upon landing in LA at a news conference: “This is not martial law. The reason we’re here is to create a safe and secure environment so you can go back to normal.” Covault said he believes the statement had a calming effect.

But 28 years later, when the police killing of another Black American, George Floyd, sparked sporadically violent protests nationwide, then-President Trump openly considered using firepower on the demonstrators, according to his former defense secretary, Mark Esper. Trump asked, “Can’t you just shoot them? Just shoot them in the legs or something?” Esper wrote in his 2022 memoir, A Sacred Trust. At another point Trump urged his Joint Chiefs chair, Gen. Mark Milley, to “beat the fuck out” out of the protesters and “crack skulls,” and he tweeted that “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.” Esper wrote that he had “to walk Trump back” from such ideas and the president didn’t pursue them.

Some involved in the current debate say they are worried Trump would not be as restrained this time. He is filling his Pentagon and national security team with fierce loyalists. The concern is not just in how much force might be used, but also whether troops would be regularly deployed to advance the new administration’s political interests.

https://www.cbr.com/of-course-superman-saved-immigrant-workers-its-what-he-does/

This topic is extremely sensitive inside the active-duty military, and a Pentagon spokesperson declined to comment. But several of the retired military officials I interviewed said that they were gingerly talking about it with their friends and colleagues still in active service.

And Mark Zaid, a Washington lawyer who has long represented military and intelligence officers who run afoul of their chain of command, told me: “A lot of people are reaching out to me proactively to express concern about what they foresee coming, including Defense Department civilians and active-duty military.” Among them, Zaid said, are people “who are either planning on leaving the government or will be waiting to see if there is a line that is crossed by the incoming administration.”

After the D.C. National Guard was ordered to clear demonstrators from Lafayette Square across from the White House in 2020 using tear gas, rubber bullets and flash-bang grenades, a group of lawyers founded “The Orders Project” aimed at connecting up lawyers and troops looking for legal advice.

One of the founders, Eugene Fidell of Yale Law School, said that the group disbanded after the first Trump administration but is now being resurrected.

“With the return of President Trump, we’re ready to help people in need,” Fidell said.

The Lafayette Square incident remains a topic of some debate inside the military community. One DC guardsman, Major Adam DeMarco, an Iraq war veteran, later said in written testimony to Congress that he was “deeply disturbed” by the “excessive use of force.” “Having served in a combat zone, and understanding how to assess threat environments, at no time did I feel threatened by the protesters or assess them to be violent,” he wrote. “I knew something was wrong, but I didn’t know what. Anthony Pfaff, a retired colonel who is now a military ethics scholar at the U.S. Army War College, said this confusion reveals a serious training deficiency: Domestic crowd control and policing “is not something for which we have any doctrine or other standard operating procedures. Without those, thresholds for force could be determined by individual commanders, leading to even more confusion.”